The Prison Engagement Initiative at the Kenan Institute for Ethics launched in 2022. Among its ongoing projects is the Duke in Prison educational initiative, which is currently recruiting Duke faculty interested in offering courses to Duke students and incarcerated students in local prisons.

Co-director James Chappel, Gilhuly Family Associate Professor of History, taught in a prison in Butner, North Carolina last year — his first experience teaching in a prison. This interview with Chappel has been edited and condensed.

When did you first become interested in working in prisons?

Before I decided to become a historian, I wanted to be a lawyer, and I interned for a few summers at a public defender’s office in Florida, which led me to spend a fair amount of time in prisons working with clients. And this was before “The New Jim Crow” — I didn’t know about any of this stuff. It was heartbreaking just to see these people — almost entirely people of color — in prison for minor drug charges, and being treated in completely inhumane ways.

When I was post-tenure, and wondering how I could do the most good in the world from the position of a tenured faculty member, I returned to that experience. I’m a Christian, and I wanted to think about how I could serve the most marginalized groups in our society from an elite place like Duke. Prison education seemed like an obvious place to go.

How did you go about teaching in prison as a Duke faculty member?

Unlike a lot of our peer schools, Duke’s Trinity College of Arts & Sciences doesn’t have a prison education program. But the Duke Divinity School does. Its program has been around for 10 or 15 years, and it’s an awesome program.

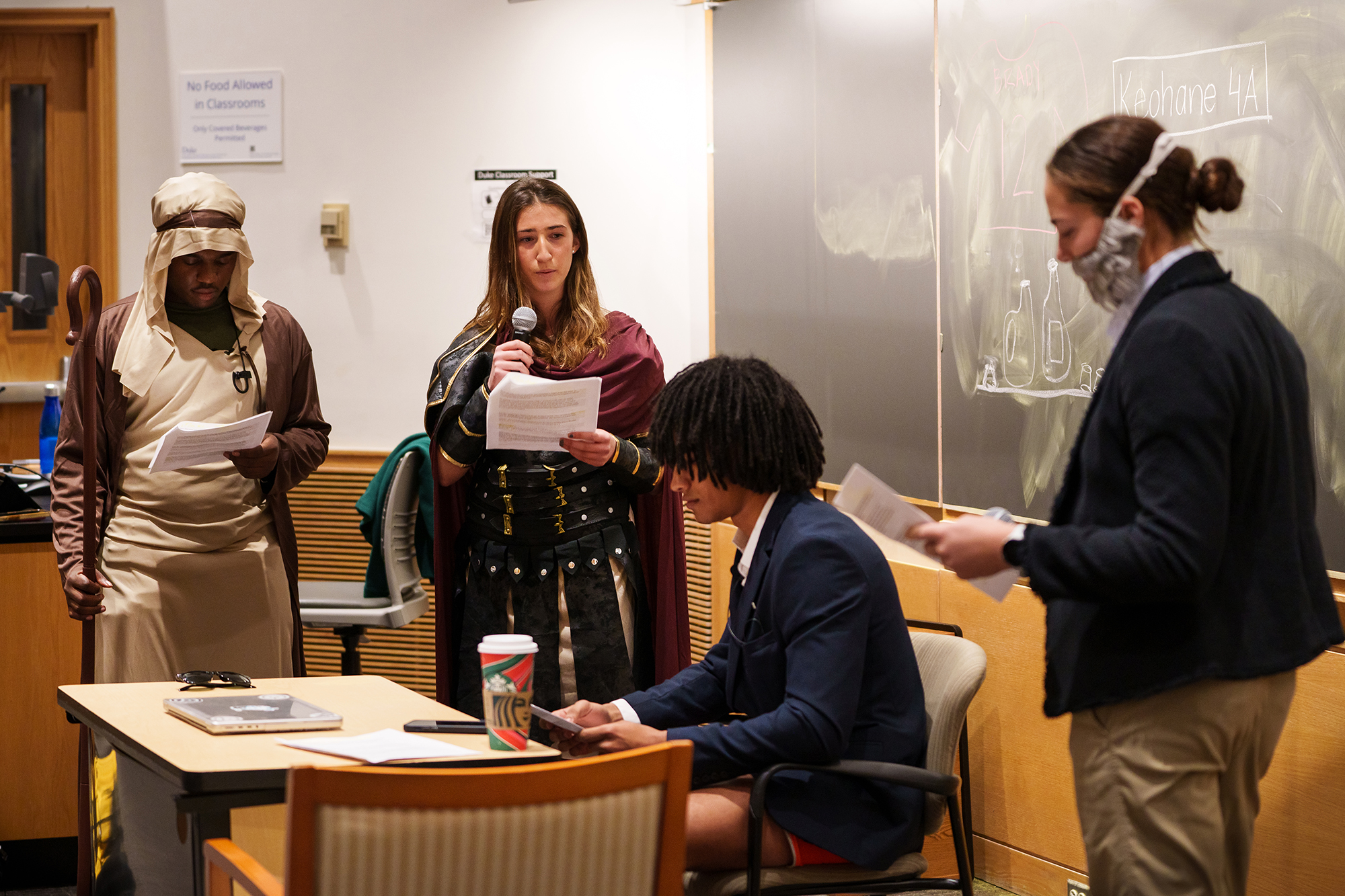

Because my academic work is on religion, I was able to put together a graduate course, cross-listed between Trinity and the Divinity School. I taught a course on the history of theology at Butner Prison last year, to a class of about 10 incarcerated people and 10 Duke students, some from Trinity and some from Divinity.

I assume you had to do background checks and go through a process to get approved to teach at Butner?

Yes, I had to go through a long training, as did all the students, about how to comport yourself in a prison. We had to be certified and fingerprinted and things like that. It was kind of a process, and it’s one of the barriers to student participation, including the fact that students have to be 21. So, basically, they have to be either seniors or graduate students. And it requires a fair amount of flexibility in your schedule. This place is half an hour away, and you have to have transportation.

What do you think motivated the students, especially from Trinity, to take part in the class?

I think students are drawn to different kinds of educational experiences. It’s important to say that is not charity work. This is not an internship. This is actual learning, alongside incarcerated people in a space where the Duke students and incarcerated students are treated exactly the same. They get to have the same assignments, they have the same grades, they have the same materials — everything’s the same. I think that’s a pretty unique experience for Duke students, to have those kinds of lateral relationships with a population that we would not generally spend time with at all.

The context right now is that we’re in a moment where many of us, whether we’re students, faculty, or administrators, are a lot more aware than we were 10 or 20 years ago about the injustices of mass incarceration, our complicity with it, and our responsibility to do what we can about it.

How did you set up your classroom to help bridge the divide between the Duke students and the incarcerated ones?

I was more worried about it than I needed to be. For one thing, I was mentored by faculty with experience in the Divinity program, and I also had a teaching assistant, Rev. Dr. Louis Threatt, who has a lot of experience in these spaces. They helped me set up the class in a way that made people feel more comfortable. We staggered the seating to make sure that there was no physical separation between the Duke students and the incarcerated ones, and we built in way more time than usual for group projects and other ways to get to know each other socially. Both communities were very interested in getting to know each other.

It probably sounds a little bit hard to believe, but it really did feel like the differences between the two student groups melted away once the seminar got started. It was incredible to see the bonds of genuine connection and friendship forming between Duke students and incarcerated students.

What was your experience like, teaching incarcerated people?

I have never encountered a hunger for knowledge or education like I did with the incarcerated students, who are so grateful to be there. They would always tell me: “This is the part of my week that I look forward to the most, because we are talking about ideas. I’m being treated like a human being. You call me by my first name, instead of by a number.”

These people are smart. It did not feel like I had to talk to or teach them differently than the Duke students. They might have less formal education, but they have skills in reading and critical thinking. In my class, in particular, we were talking about religion, race, and power. In addition to their academic knowledge, which many of them did have, they also had life experiences that gave them, in some ways, a lot more insight than Duke students into how these things operate in the world.

I think a lot of Duke students — and Duke faculty, to be honest, including myself — we know the numbers. We know how bad it is. But it is a different feeling to spend two hours with these people talking about scholarly stuff, and then half of the group gets to go home, and half of the group doesn’t. The door slams behind you, and you see them walking back to their cells. And your heart just breaks for these people.

I think anybody who does it leaves thinking, “I can’t abandon these people.” We were allowed to have some email correspondence with the incarcerated students during the class, and at the end, one of them sent me this heartbreaking note that ended with “Don’t forget about us.” I think they feel so forgotten, and they are so forgotten.

One of the moral challenges of our time is: What can we do? What can we do from where we are? And because of where we sit at Duke, there is something we can do for this population. It’s something small, and it won’t solve the problem, but it’s something important nonetheless.

What can people at Duke do to help incarcerated people?

I want to acknowledge that there is already a lot of great work going on at Duke. The Prison Engagement Initiative was founded by the leaders of the Divinity School program, and it spent the first year of its operation doing a survey about what kind of work was happening at Duke. And a ton of work is happening at Duke. A lot of people are working on mass incarceration, especially in the Law School and in Public Policy. We want to build on that work and add to what Duke is already doing.

We are starting a Duke in Prison educational initiative, which will be led by myself and Chris Wildeman in Sociology. We are trying to bring together faculty who are interested in this work. Within, let’s say, the next two years, we hope to have a pipeline of classes between Trinity and a local prison.

Even if faculty aren’t sure they’ll be able to teach a whole class, they can still come in, because there are other opportunities — for instance, just coming in and giving a lecture about your research. Also, it’s important to say that if you want to get into this work, you’ll be trained. I had access to a lot of support.

The Prison Engagement Initiative is also organizing a Piedmont Prison Consortium, which is bringing together interested faculty from, right now, NC State, NC Central, and UNC-Chapel Hill. We had about 30 people from those schools at Kenan for a launch meeting in January. It was so exciting to see undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, and administrators from across the region who are drawn to this work. We hope to move this forward with the help of Kenan, Duke’s new Center for Community Engagement, and university and community colleges across the Triangle region.

The goal is to set up a bachelor’s degree-granting program for incarcerated people. It’s very hard to get that set up. It requires a lot of classes. You have to deal with admissions, financial aid, degree credit transfers, and more. We’ve been working very hard on this, and we think it’s possible. We need help, though, so I hope that if anyone reading this feels called to this work, they’ll drop me a line. There’s always more to do.

An interest meeting for the Duke in Prison educational initiative is scheduled for Monday, February 19, 2024, at noon. If you are a Duke faculty member interested in joining, please email James Chappel and Chris Wildeman.