rLab Students Share Research on Pathways to a “Happy City”

On a Sunday afternoon in April, a group of students gathered in a Duke classroom to present their research.

This wasn’t for a class: they were passionate enough about the theme to work on these projects on their own.

Driven by the conviction that we need to reimagine current systems – especially the ones driving climate change – the Regenerative Futures Lab, or rLab, is a place for students to envision big societal changes that prioritize human and ecological wellbeing.

“Regenerative thinking is a mode of economic thought that centers wellbeing, justice, reciprocity, and care,” said Emma Williams, one of the group’s facilitators, as she introduced the presentations.

Unlike other labs in which the research agenda is set by a faculty member, rLab is primarily student-driven. This meant that the students had to decide not only what they were going to do in rLab, but how they would do it.

The first semester was a challenge, and there were inevitable mistakes. For example, one student team wanted to survey community members experiencing food insecurity in order to center the perspectives of people most directly affected by the problem. But they were too late to get approval from the Institutional Review Board, which oversees research using human subjects.

“It’s a tall task to ask people to think outside educational structures – especially for those of us who didn’t know what IRB is,” Williams joked.

“We’re very successful in structured environments with guidelines and guardrails,” Dirk Philipsen, rLab’s faculty advisor, told the students. “It’s not so easy to do this in an environment that we self-create.” Still, he said, “the process of how we’re doing it needs to match the vision.”

rLab is democratic and de-hierarchized. The students collectively decide on a theme related to regenerative thinking, form teams, select research projects, determine their scope, and collaborate on them. First, they work to understand the many facets of a social problem, then they research existing resources and proposed solutions, then they identify pathways to transformation and potential challenges. A small group of facilitators help the others stay on track.

This semester, the students chose the theme of “Building a Happy City.”

“What systems are at the root of food insecurity and how can communities dismantle them, especially in Durham?” said Sophie Lair, opening her team’s presentation.

The students interviewed many experts in Durham, including food security coordinator Mary Oxendine. The interviewees were “adamant” that food insecurity is primarily an economic problem, not an access problem. “There is limited evidence for a causal relationship between geographic access and food insecurity,” said Emely Arredondo.

There wasn’t one primary cause of food insecurity, the students said. Instead, it was “a complex web of interactions between multiple factors,” including social attitudes that undergird policy.

“There is an interaction between who we believe deserves to eat and the federal policies that shape how people get access to food,” Aaron Lam said.

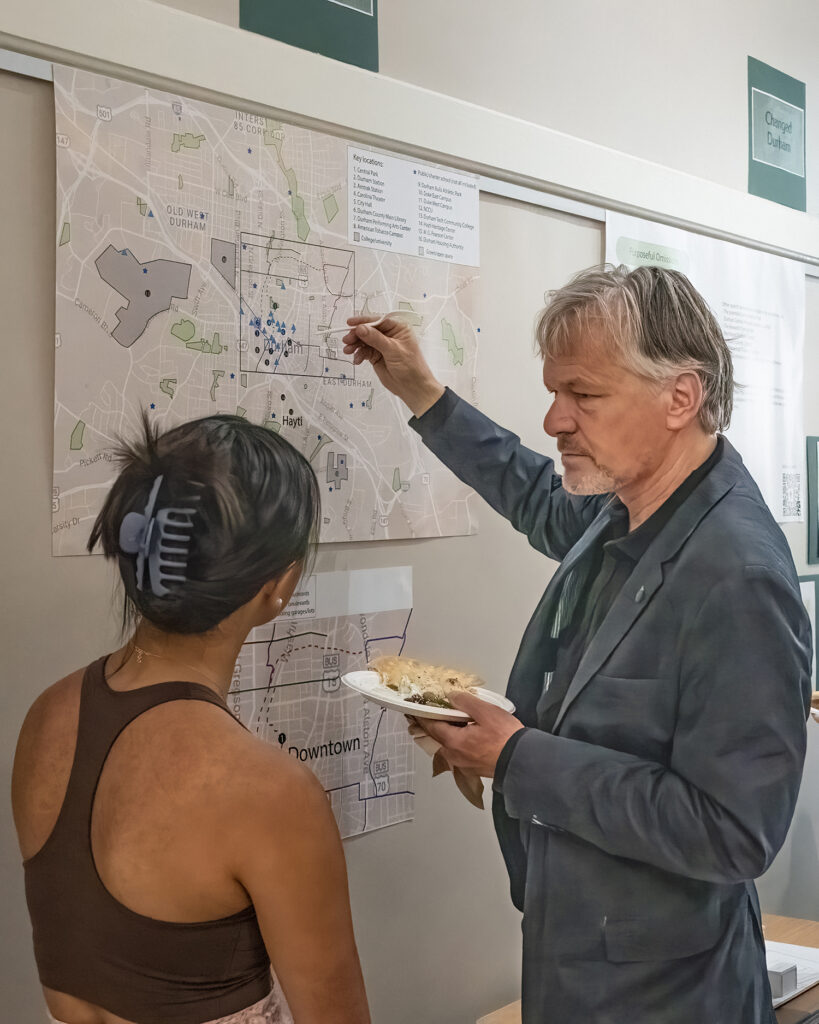

The second team focused on rethinking Durham as a regenerative city. They noted that Durham is in a period of economic expansion, but while its population is increasing rapidly, “growth is overriding care.”

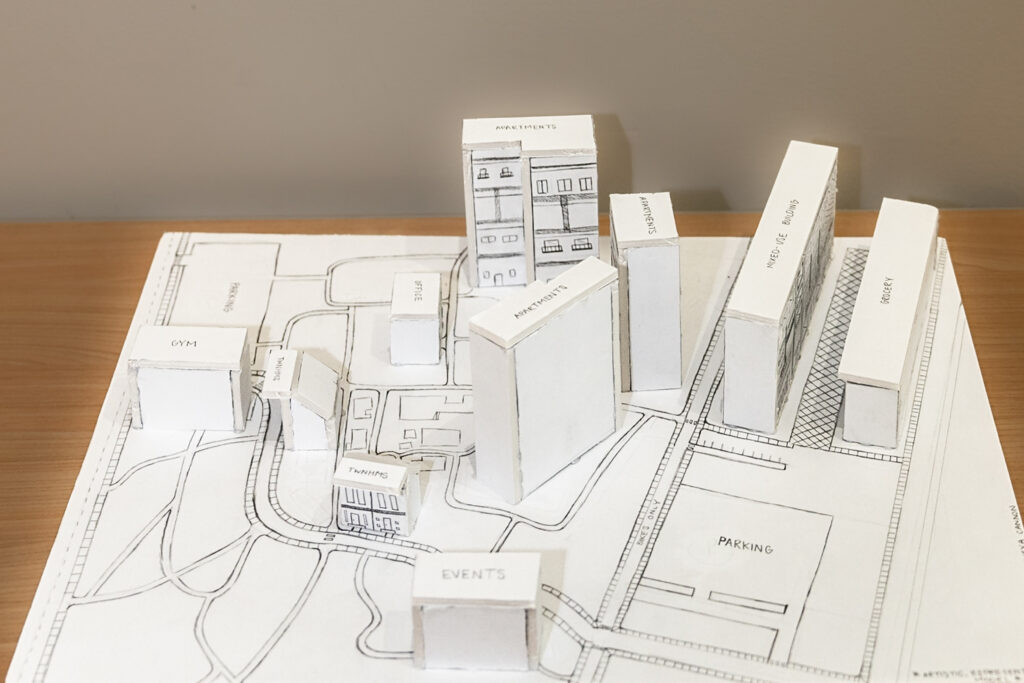

The students said they spent a lot of time exploring Durham, but they chose to focus on a much smaller area, Duke’s Central Campus, as a site for envisioning regenerative structures. They created an exhibit featuring a model that includes a mixed-use building with space for Durham small businesses.

Based on the concept of the 15-minute-city, their exhibit also included several imaginary routes by which people could move through a city throughout the day, from home to work and other spaces in-between. One of these routes included a stop at a cemetery.

“To be truly regenerative we need to re-examine how we interact with death,” said Jason Kreinberg. “The ways we interact with death are taboo, sad, avoidant. Cemeteries should be welcoming, not repelling.”

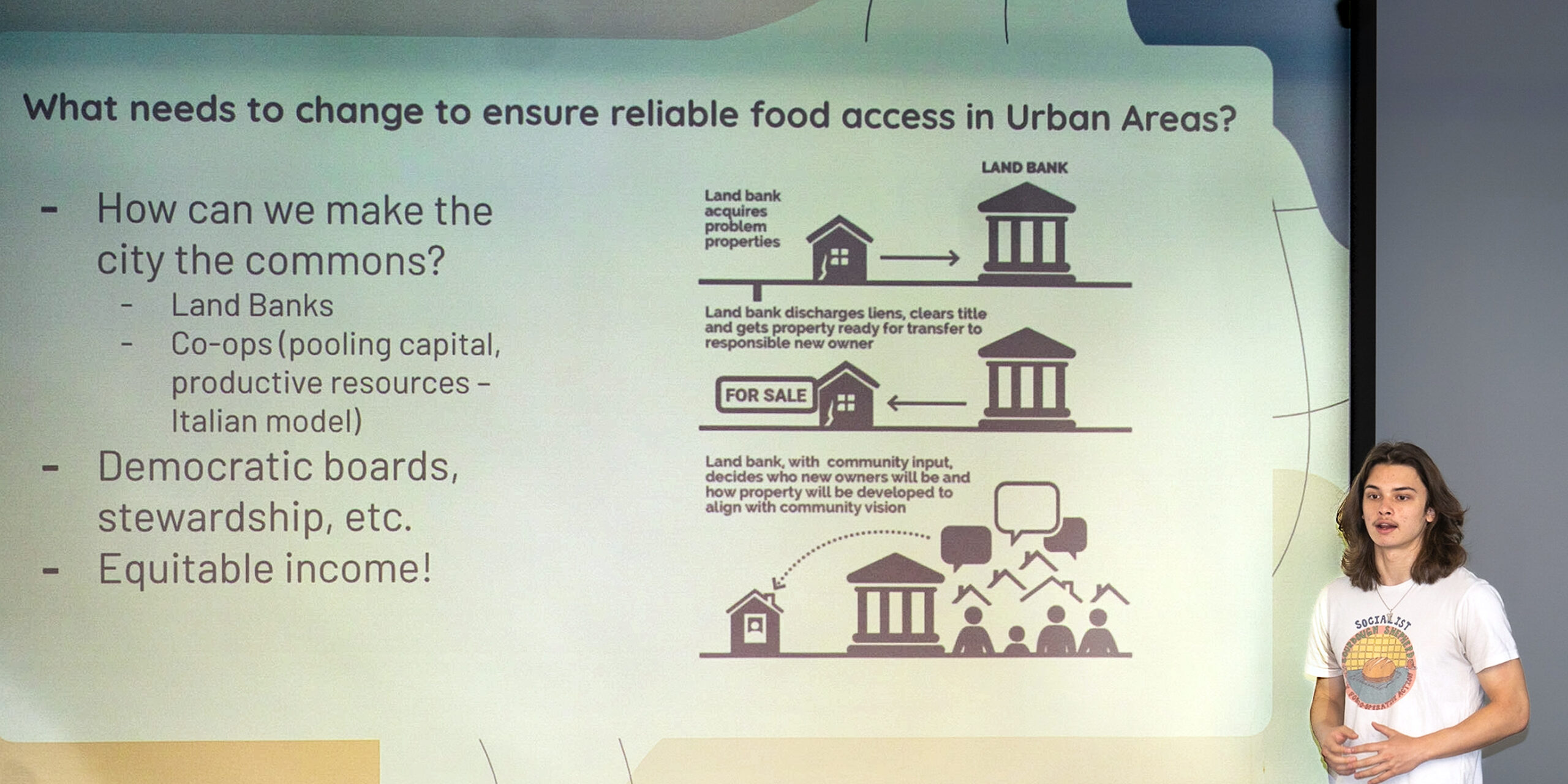

Throughout the presentations, the students were candid about the scale of problems like food insecurity and gentrification, but they maintained that change was possible. To address food insecurity, for instance, they discussed land banks and agricultural cooperatives as “compelling solutions.”

“What would Durham look like if we had agricultural cooperatives that employed significant numbers of people?” offered Kerrina Good.

The focus remained on how systems impacted people.

“All of this is based in how we consider ourselves as community members,” said Emma Williams.

rLab is currently accepting applications for the 2023–2024 academic year. The theme is “Debt — What We Owe to Each Other.” Read more and apply here.