“I don’t care about art. I care about the future of the planet.”

Kliën has always had a tendency to experiment. As a teenage painter, more interested in the artistic process than its results, he immersed himself in paint and threw himself against his canvases. In the early 2000s, as a young choreographer, he became fascinated by artificial intelligence and machine learning, and he created a “nonlinear ballet” that would rearrange itself according to an algorithm, producing different dance sequences every time.

It was an interesting experiment, he says. But “after 2001, I just stopped all interest in technology. It was almost like overnight I decided that technology is not the salvation that I thought it was.”

In fact, he relinquished the “salvation model” altogether—the notion that someone brilliant will come along with the next “great idea.” This concept, he says, permeates Western choreographic practice and Western thinking in general, to its detriment.

Instead, he says, “I got more interested in working with the dancer as a living, breathing organism, rather than seeing them as moldable matter that I can manipulate to my own will. I didn’t think that made ethical and political sense, I didn’t think it made ideological sense, and I didn’t think it could produce a result beyond what I knew already.”

Instead of salvation, he thought, “maybe we should go more for revelation.”

The “politics of revelation” has guided his work since. He was also influenced by the systems theory of cultural anthropologist Gregory Bateson, which helped expand his idea of what choreography could be into “interrelational, interpersonal dynamics.”

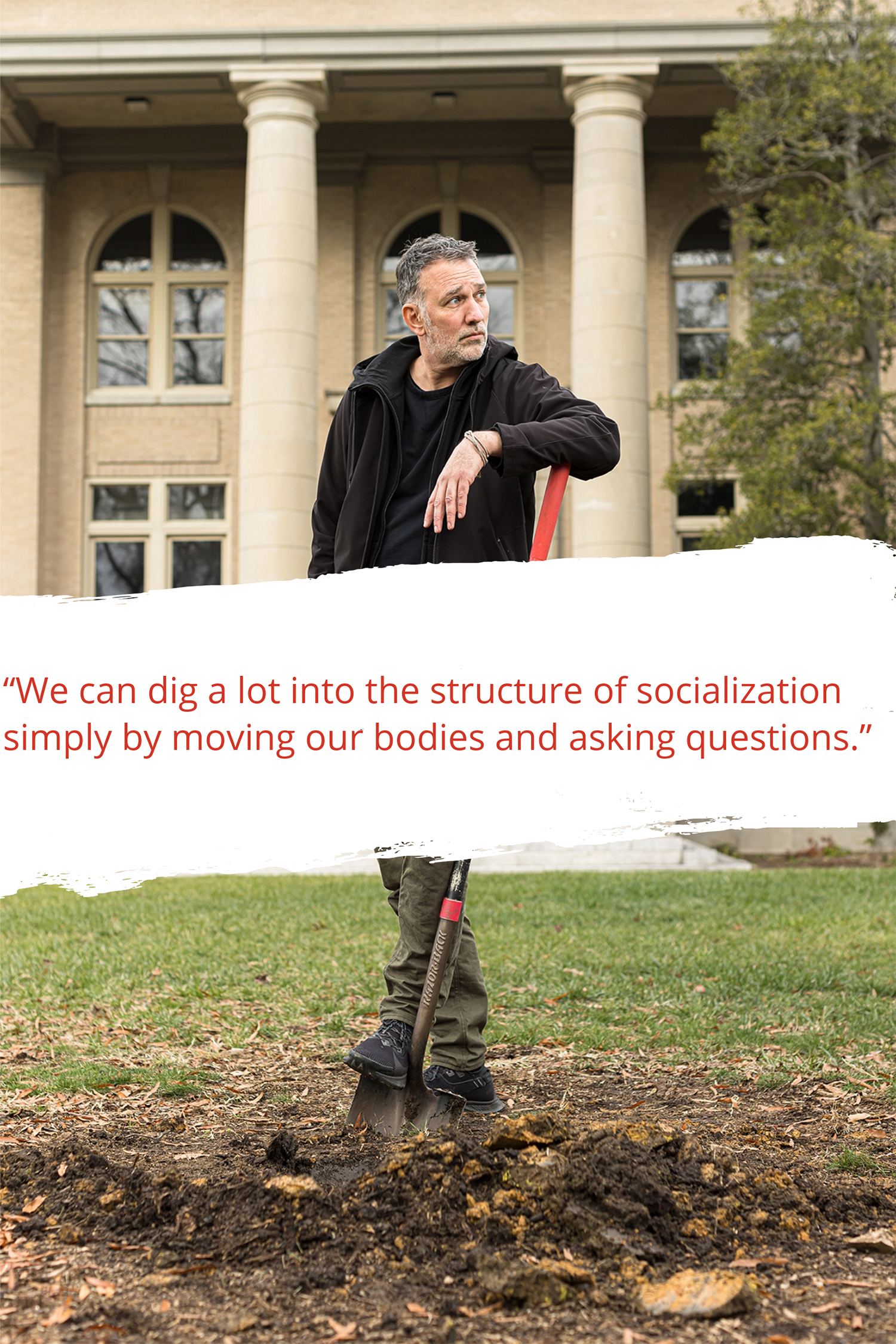

“There’s this great Seamus Heaney poem, where he talks about his ancestors having been farmers in Ireland and digging the ground, and he only has his pen, but he will dig with it,” Kliën says. “I always think, ‘We have our bodies. Let’s dig with them.’ We can dig a lot into the structure of socialization simply by moving our bodies and asking questions. And people think it’s indulgent, but actually, it’s a necessity. It’s crazy if somebody doesn’t do it, because then you take a reality for granted that is completely and utterly constructed, and at the same time, absolutely and utterly hidden from you.”

According to Kliën, “there are structural, systemic dynamics at play in each of us that create an unhealthy society. We have a destructive thinking in the way we relate to our environment that leads to climate change. So there are all these things that can be discovered, but they need time, space, and resources. And for me, the artists are, hopefully, the people who are resourced by society to put their feelers out, to put their entire perceptive system at stake, in order to sense things that are not right, so that we can correct course.”

Too often, Kliën says, the art we embrace doesn’t challenge power structures, but reinforces them.

“If you look at the dancers we celebrate as a society, they’re mostly the people who do very narrow movements very well, and can perfectly repeat them.” He wonders about the ethos this embodies. “Why do people want to see chiseled bodies, moving in a pre-agreed way, that displays some kind of mastery beyond what anybody else can do?

“I can enjoy mastery when I listen to a Bach cello concerto. But it’s one thing to say, ‘Yes, I enjoy it,’ and another to ask, ‘Is it what the world needs?’”

“I can enjoy mastery when I listen to a Bach cello concerto. But it’s one thing to say, ‘Yes, I enjoy it,’ and another to ask, ‘Is it what the world needs?’”

What the world needs, Kliën says, are institutions that function within communities like “wild organisms,” creating public spaces where relationships are created and revelations can unfold. As an example, he discusses an arts center he ran in a deconsecrated church on the west coast of Ireland, which had a collaboration with a nearby center for adults with learning disabilities, primarily Down syndrome. Kliën and his collaborators invited the group to dance with them and started a relationship based on mutual curiosity, which he says “was against the common wisdom of the time, but was certainly responsible.” This relationship entirely shifted the culture of the center. Eventually, the group formed a dance company, and many initiatives grew out of the collaboration that are still active across the world today.

Kliën believes that cultural—not technological—solutions are necessary to envision radical new possibilities for human society. His ultimate vision is a culture where dance is not simply “an entertaining thing,” but “becomes crucial to the discourse in the wider community, and contributes to its intellectual life.” He’s found that the best way to generate new ideas is in a group, and that sensing, moving, and thinking together is the best way to build trust among the group’s members, so that no one feels threatened by the possibility of saying the wrong thing or moving the wrong way.

In order to construct a space where this can happen, he says, “You go, ‘How can I create the conditions for you to feel more free? To feel more liberated?’”

This is why Kliën tells collaborators “Don’t be creative” and “Don’t try to try to be meaningful.” It’s freeing. It gives rise to new ideas.

Besides, he says, “You’re already meaningful.”

Writing: Sarah Rogers

Photography: Justin Cook

Photography Assistants: Alex Boerner, Allie Mullin

Photo Retoucher: Lindsay Warren