In early December last year, I gathered online with other Duke graduate students who had been awarded a GradEngage Fellowship to work with a Durham-based community organization. We discussed what it meant to “work on” or “work for” or “work with” issues and people who were the focus of these organizations. As we talked, I remembered a probably apocryphal story of John F. Kennedy proudly telling Jawaharlal Nehru of Kennedy’s plan to establish the Peace Corps so American young people could live in and render assistance in countries across the planet. Nehru, the story goes, smiled, nodded, and said, “oh, that will be wonderful for the American youth.” That story was also on my mind when a few years ago I flew to Kigali, Rwanda, for a teaching position in which I’d work with gifted and talented Rwandan high school students, helping them prepare for and succeed in U.S. universities. During the flight, I realized by overhearing conversations that I was seated among several rows of Americans who were traveling to Africa for a few days of some sort of aid work. I smiled– smirked, really– to myself at the revealing use of the name “Africa” as a destination, as if a place so vast and diverse could unproblematically be described so monolithically. Who were these “aid tourists” really interested in? Were they collecting a badge of some kind? Creating a line on a resume or application? And yet, there I was, an American, descending, literally, to bring a kind of assistance to a place and people in some kind of need, getting paid in the process. And here I am, mentioning that experience in the context of discussing another project to which I’ve offered aid and assistance.

In early December last year, I gathered online with other Duke graduate students who had been awarded a GradEngage Fellowship to work with a Durham-based community organization. We discussed what it meant to “work on” or “work for” or “work with” issues and people who were the focus of these organizations. As we talked, I remembered a probably apocryphal story of John F. Kennedy proudly telling Jawaharlal Nehru of Kennedy’s plan to establish the Peace Corps so American young people could live in and render assistance in countries across the planet. Nehru, the story goes, smiled, nodded, and said, “oh, that will be wonderful for the American youth.” That story was also on my mind when a few years ago I flew to Kigali, Rwanda, for a teaching position in which I’d work with gifted and talented Rwandan high school students, helping them prepare for and succeed in U.S. universities. During the flight, I realized by overhearing conversations that I was seated among several rows of Americans who were traveling to Africa for a few days of some sort of aid work. I smiled– smirked, really– to myself at the revealing use of the name “Africa” as a destination, as if a place so vast and diverse could unproblematically be described so monolithically. Who were these “aid tourists” really interested in? Were they collecting a badge of some kind? Creating a line on a resume or application? And yet, there I was, an American, descending, literally, to bring a kind of assistance to a place and people in some kind of need, getting paid in the process. And here I am, mentioning that experience in the context of discussing another project to which I’ve offered aid and assistance.

Can helping an other ever be fully separated from what’s in the act for oneself? Must it be so for the help to be ethically acceptable? Our internet-driven language has given us the term “humble brag,” which implies an emphasis on the self end of the continuum, but is the other end of the continuum ever what helping is fully about, even if there’s no brag or any public mention of an act of help?

An often-discussed idea in evolutionary biology is an equation developed by William Hamilton, which calculates that a gene for altruistic behavior might spread if c < rb, where c is the cost to the altruistic individual, b is the benefit to the recipient of the altruism, and r is the relatedness between the altruist and the recipient. This mathematical statement was a descendant of an idea described by biologist J.B.S. Haldane who said he would jump in a river to save two brothers, but not one, and eight cousins, but not seven. Both are expressing the notion that when we help others, those others tend to be very close to self, so much so that we share most of our genes. Subsequent work on the nature and evolutionary origin of altruism pushes and stretches this direct genetic linkage, suggesting that a tendency toward helpfulness, or feelings that incline us to help even those to whom we’re not related, may in fact be one of our species superpowers, enabling cooperation of non-kin individuals on a scale shown by no other species. Duke evolutionary anthropologist Brian Hare explores these questions of helpfulness and friendliness in much of his work, including his latest book, Survival Of The Friendliest: Understanding Our Origins and Rediscovering Our Common Humanity.

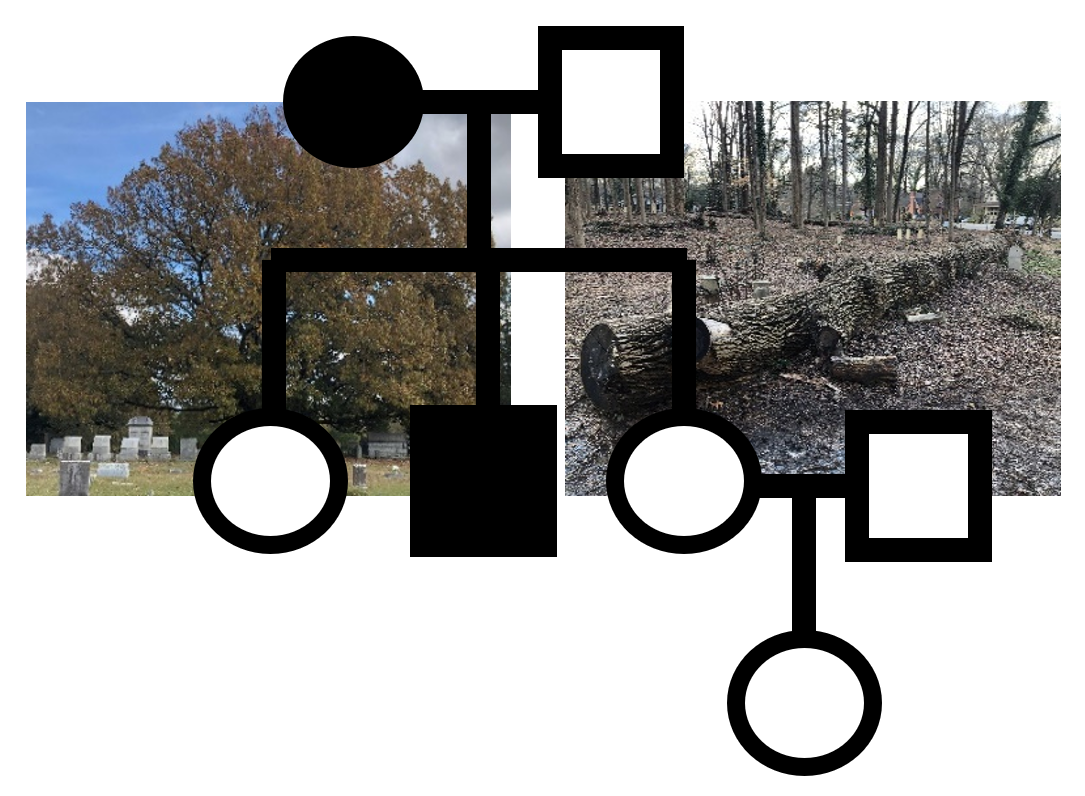

In the case of my work with the Friends of Geer Cemetery (FoGC), who is the work for? Is it for those buried in the now-neglected cemetery? Yes, and clearing and ultimately restoring graves and celebrating stories honors those whose resting places have been neglected. Is it for the descendants of those buried there? Yes, and one of the goals of FoGC is to locate descendants and share with them what is being learned about their ancestors, engaging them in the group’s projects and decision-making processes. The interest and excitement of some descendants when contacted shows the value they see in FoGC’s work. The reluctance and silence of other descendants, perhaps indicating skepticism and caution, suggests some of the complexities and tendrils that this work entails. Is the work for the broader community of Durham and, perhaps, the larger American society? I hope so.

I have no ancestors buried in Geer Cemetery. And yet, the projects of FoGC do benefit me — benefit all of us. While I might and must wrestle, in humility, with the ethics of “helping” and “working for, with, or on,” I know deeply that I, we, all of us, are impoverished in powerful ways by systems and structures that have and continue to devalue and deface the lives and stories of one group of people, however we might define them, while valuing the lives and stories of other, more dominant groups. Maybe that’s just something I imbibed growing up with a religious version of “love thy neighbor,” but I suspect it’s something more, a kind of impulse and instinct we’re only beginning to understand in ways we might call science. If this is part of what we mean by saying a thing that makes us human, we imperil our humanity by ignoring it in a strong sense, as I argue happened in the creation of separate and unequal cemeteries in Durham, or in a weak sense, by doing works of social justice with self-interest at the fore. The path between those edges may be narrow but it seems a vital path to walk, and to do so with urgency and care.