In April 2020, the Rights Writers were asked what perspectives have been left out of the major debates on their topic, and how would including them increase understanding or contribute to progress on this issue.

In my previous blogs, I described how ethnic enclaves could serve as protective mechanisms for immigrants around the world. These enclaves provide some of the most vulnerable populations with social and economic support with the insulation of ethnically homogeneous neighbors, local businesses, and other cultural features that ease immigrants’ transition into their host countries. They are seen as safe spaces that could simultaneously ensure the protection of an ethnic group’s human rights while also providing value to its local governing body. While ethnic enclaves aren’t perfect, where in some cases they’re seen as places that stunt immigrants’ ability to assimilate into their local societies, they provide crucial economic stability to the populations in question.

Although I’ve covered a breadth of focuses in my research, I found that the major debates surrounding my topic haven’t been able to successfully quantify the ethnic enclaves’ impact on undocumented immigrants. This is largely due to the fact that most statistics about the undocumented immigrants who reside in ethnic enclaves are (very understandably) “off the book”. As a result, there is no way to truly encapsulate the unique experiences of ethnic enclaves’ undocumented inhabitants. This inhibits our current ability to fully analyze their aggregate long term outcomes in relation to economic trends of documented immigrants living in the enclaves, and other quantifiable data. Although I don’t have a solution for this gap in information, I can see the temporal relevance in analyzing undocumented immigrants within ethnic enclaves especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a time where most citizens are extremely vulnerable to the combined health, social, and economic effects of COVID-19, one can only imagine the toll that the pandemic would have on undocumented immigrants, even if they have the social protection of living within an ethnic enclave.

I think that the most difficult part about reconciling with the harsh reality of COVID-19, is knowing that the effects of the virus itself and the ensuing turmoil will devastate many families for years to come. Just in the month of March, the U.S. unemployment rate rose by almost 1 percentage point to 4.4 percent. To put things into perspective, this is the largest over-the-month increase in the unemployment rate since January of 1975; over 5.7 million jobs were lost over the course of last month. While this has left many people at risk, the population that I’m very concerned about are the undocumented immigrants who don’t have an economic safety net that many unemployed Americans rely on (unemployment rate numbers don’t factor in undocumented workers). A large majority of this population does not have access to government welfare benefits such as food stamps and social security. Instead, many families’ well-being depends on their ability to earn a constant revenue stream through work. And in many cases, their work has been taken away from them.

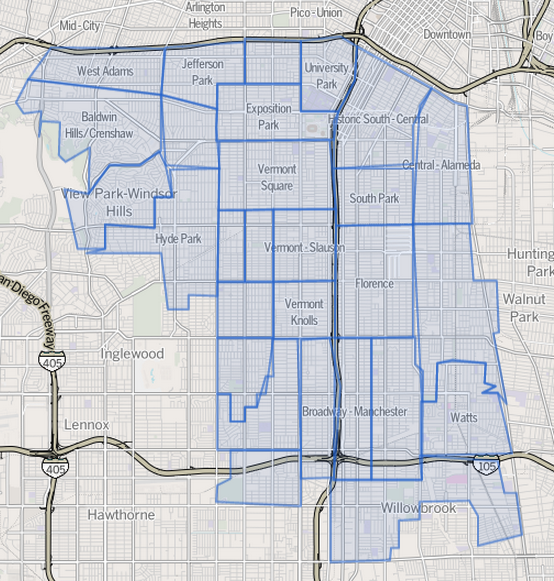

For example, while an ethnic enclave may provide an ethnic immigrant population with a certain amount of insulation from society, these benefits may be miniscule compared to the economic and social hurdles that documented and undocumented immigrants have to overcome in order to survive. In the case of Long Beach, CA, which is home to the Cambodian ethnic enclave Cambodia Town, immigrants tended to concentrate in industries such as: maids and cleaners, cooks, and production workers. With the advent of COVID-19, many of these jobs that were occupied by immigrants who lived in these ethnic enclaves were deemed “non-essential,” and therefore either furloughed or laid off. Undocumented immigrants who had work in these sectors would not only lose their jobs, but also be unable to file for any unemployment insurance or government safety net such as welfare or the newly passed stimulus plan, the CARES Act. At the same time, many workers in jobs such as janitorial services, food service, and agriculture are deemed “essential,” yet those jobs typically do not provide benefits that would help them overcome the sheer disruption caused by COVID-19.

Ultimately, this time will shed a new light on the discussion surrounding human rights and the country’s undocumented populations. I believe that the U.S. has an ethical obligation to support its “residents,” but simultaneously, it has an obligation to serve its citizens first and enforce its laws. In the case of COVID-19, here’s the dilemma. Yes, we must exercise social distancing, the closure of “non-essential” businesses, and any preventative measure to put an end to COVID-19. But at the same time, the longer we wait, more people will be out of jobs and may suffer from devastating economic consequences. In order to protect the human rights of undocumented immigrants across the nation, regardless of whether they reside in ethnic enclaves or not, there needs to be a mutual effort between policy makers and local economic drivers to protect the unprotected; something that can be achieved with more empathetic decision-making that doesn’t rely solely on partisan or economic agendas.

Looking at a more long-term approach, I believe that our current crisis will transform our way of thinking about this debate. Discussions surrounding human rights as they relate to our moral and ethical obligation to ensure the wellbeing of people will transcend all economic and judicial motives. Ultimately, instead of rationalizing decisions that place things before the wellbeing of people, we should ask ourselves, “what ought we do” to make the world a better place for mankind.