Students Reflect on Wilmington’s Histories with Community-Centered Art

Written by Elizabeth Thompson, Trinity Communications, with additional reporting by Sarah Rogers, this article was originally published on Duke University’s Trinity College of Arts & Science website as “Cultural Anthropology Students Learn from a Buried Past.”

Few college students would volunteer to spend a Sunday afternoon in a graveyard, but members of the Fieldwork Methods class in the Department of Cultural Anthropology arranged this trip themselves. They are in Wilmington, North Carolina, visiting the sites of one of the darkest events in the state’s history: the white supremacist coup that destroyed the city’s prosperous Black community in 1898.

Their class is part of America’s Hallowed Ground, a multi-year project developed by professor Charlie Thompson and actor and playwright Mike Wiley, an artist in residence at the Kenan Institute for Ethics.

“America’s Hallowed Ground challenges us to consider how we respond to locations that have been the scene of violence and sacrifice,” Thompson said. “We are asking students to engage with local communities, really listen and consult with the people who are still living with the legacies of these events, then create artistic responses that honor and elevate this often-overlooked history.”

On November 10, 1898, white mobs ousted democratically elected African Americans from city government and reinstated the white-only rule that had existed before the Civil War. The exact number of Black male citizens of Wilmington who were murdered during the coup is unknown, but estimates range from 60 into the hundreds.

In the days that followed, Black women and children hid in Pine Forest cemetery on the outskirts of the city, hoping to find refuge from persecution.

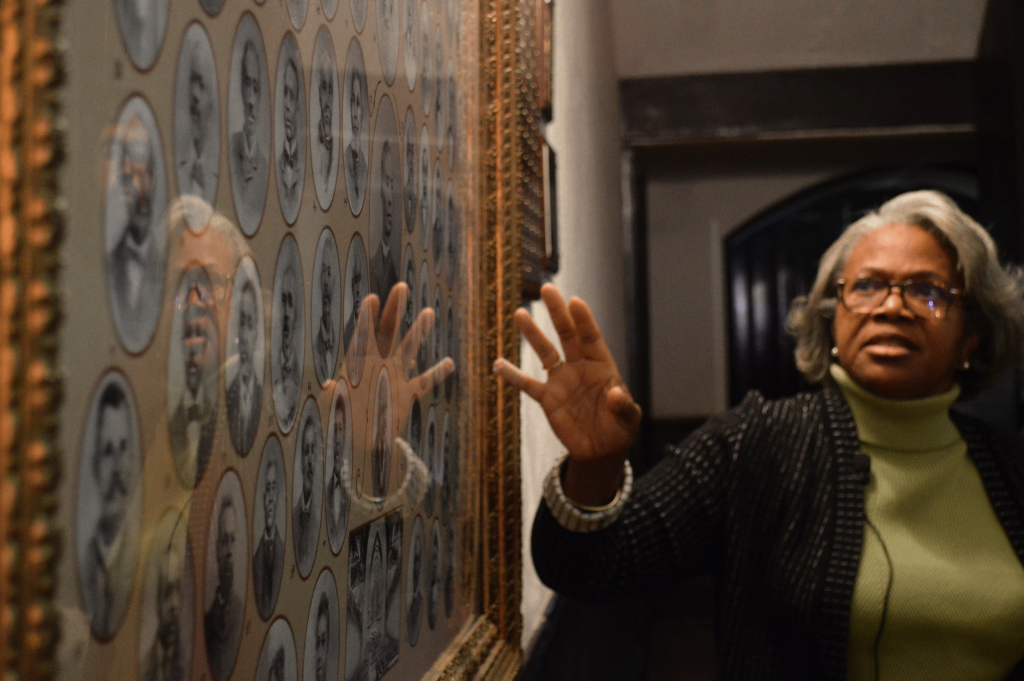

It’s a hot afternoon in April when the students gather among the gravestones with local historian Cynthia Brown, whose great-grandmother was among those who fled to Pine Forest. Brown, and many other descendants of 1898, are dedicated to uncovering the history of what happened that November and its long-term effects on Wilmington’s Black community.

Pine Forest Cemetery is the next to last stop on a weekend that has jolted the students between the present and the past, the 21st century and the waning days of the 19th. In partnership with guides like Brown, they have visited the site of The Daily Record, the Black-owned newspaper which was burned during the coup; St. Stephen AME Church, a spiritual center and gathering place of the Black community in 1898; and the Cameron Art Museum, home to Duke University art professor Stephen Hayes’ sculpture Boundless, which honors Black U.S. troops who fought at the Battle of Forks Road during the final weeks of the Civil War.

As the students interact with community members, they are practicing ethnographic skills such as interviewing and observation in a real-world setting. They are also forging an emotional connection to the people they encounter and the sites where the events of 1898 unfolded. When they return to campus, they will channel these experiences into projects that combine research and artistic expression.

Rebekah Alvarenga, a junior majoring in Cultural Anthropology and Visual & Media Studies, has planned a visual art project. In a series of five collages titled “Wilmington Landscapes,” she layers photos from Wilmington’s past and present with newspaper articles, signs and landmarks to build a nuanced response to the coup and its reverberations down the decades. “I want to connect 1898 to today,” she explains.

When asked about the open space left at the top of many of the collages, Alvarenga replies that she left it there so that the images “had space to grow and change.”

Huiyin Zhou, a sophomore, is combining archival materials and her own photographs taken on the trip into a multimedia project called “Remembering Wilmington 1898.” “My project consists of three found poems and four-photo series,” she said. “To be honest, I didn’t know where to start on my project until I came here.”

Even the brochures at the Hampton Inn where the students spent the night provided material for Zhou to ponder.

“I’m interested in the collective memory surrounding 1898 Wilmington. At the hotel, there’s an advertisement for Poplar Grove Plantation — horse-drawn carriage tours and ghost walks for tourists. But what kind of ghosts are people focusing on? The ghost of white supremacy is still alive.”

While the students reach back through the years to honor the victims of the coup, they also recognize the importance of the bonds they’ve forged with the descendants of 1898 and each other. “I am indebted to all the community members who shared their time, experiences, knowledges and presence with us,” Zhou writes in the introduction to her project. “I am also grateful for all of my fellow students who have collectively formed a community.”

Building community is an integral part of the students’ introduction to ethnographic research. Back in Pine Forest cemetery, Durham teaching artist Aya Shabu, who accompanied the class to Wilmington, leads the students, teachers and community guests in a flocking exercise.

They stand close together, each in turn raising an arm, looking at the person beside them, or taking a step forward. The others follow suit, like a flock of birds following the leader. It’s a slow, mesmerizing dance as gesture succeeds gesture.

Shabu encourages the students to move with reverence into the experience of being in this place, to feel it with their whole bodies. Then, she asks them to distill their thoughts about the weekend into one word.

“Mourning.”

“Migration.”

“Legacy.”

“Maybe.”

The flock breaks apart and the students move off into the cemetery, alone or in small groups, to continue exploring.

America’s Hallowed Ground, a project of the Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University led by Charlie Thompson and Mike Wiley, will continue in spring 2023 with an exploration of the Trail of Tears and its legacy.