Playing with Ideas: How “The Good Life” Brings Students Together to Ask the Big Questions

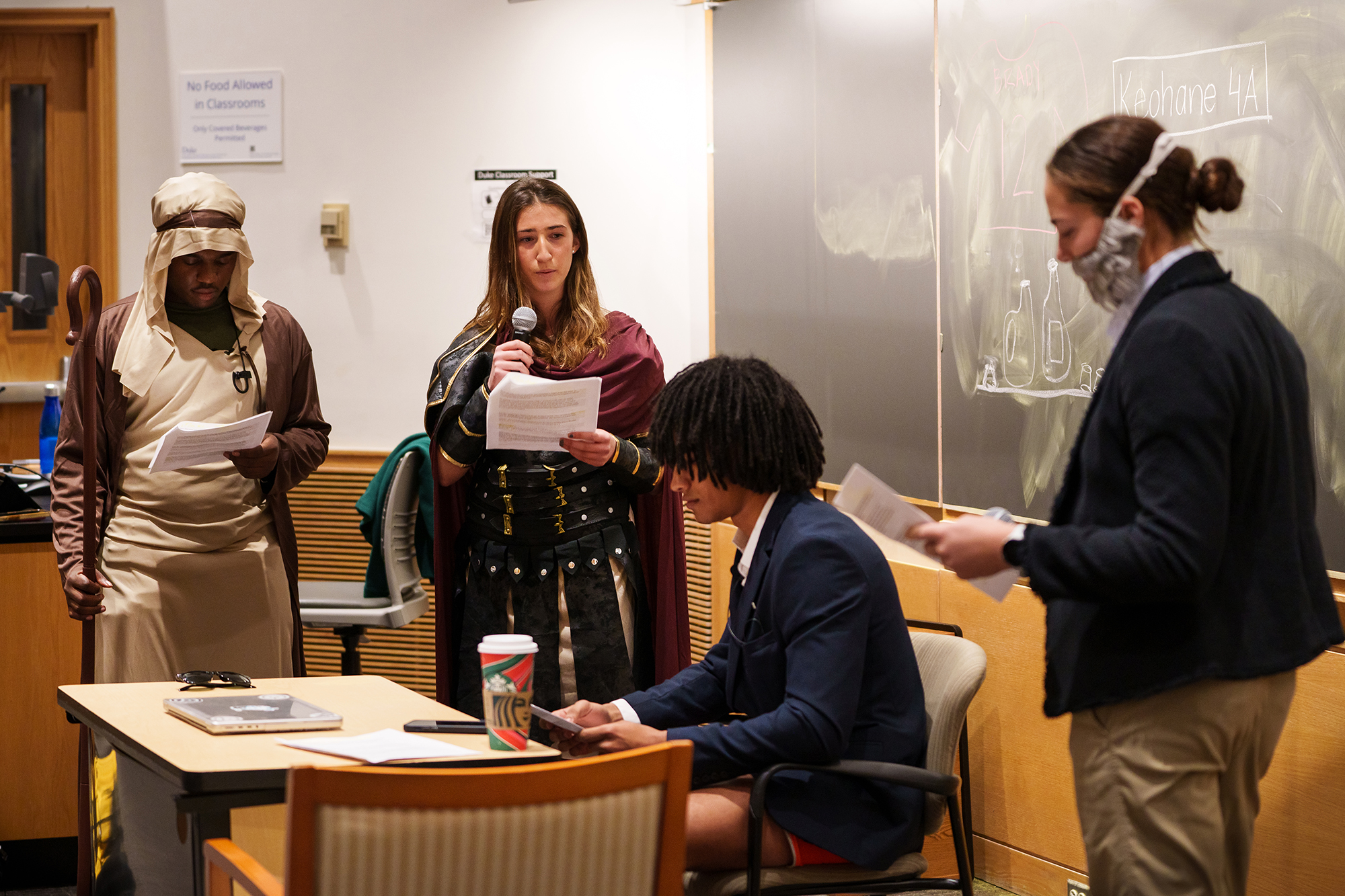

The class is scheduled to begin at 1:25 p.m., but ten minutes later, students are still chatting and settling into their seats. Others are milling around at the front of the lecture hall, looking over pages of printed notes. Three are costumed: a Roman soldier, a robed Nazarene, and a bearded professor. The screen overhead projects a paused video of a TikTok feed.

The professor finally calls the room to order. “Sorry we’re late getting started,” he says. “The tech guy took a while to figure things out.”

The joke is that the professor, Jed Atkins, is the tech guy: the students needed some help figuring out how to turn on the projector’s sound.

The class is “The Good Life,” an exploration of philosophical, religious, and scientific thinking across the centuries on life and its meaning. For one of the students’ final assignments, they write and perform dialogues representing three of the traditions they’re learned about in the course.

If you’re visualizing white-haired philosophers in robes, issuing ponderous thoughts in turn — don’t. Instead, think “Saturday Night Live.”

The first skit focuses on a Duke student who is rejected for a coveted position at Goldman Sachs, sending him into an existential tailspin as he grapples with his life not going perfectly to plan.

“So over!” he says in frustration. “What am I going to do now?”

Scrolling through TikTok, as projected on the classroom’s screen, he watches a video with a voice-over from an inspirational quote from Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius. A red heart floats up the screen as he “likes” the post, drawing laughter from the lecture hall.

Soon the young man is visited by Marcus Aurelius himself — the student in the garb of a Roman soldier — along with Jesus of Nazareth and Duke philosophy professor Alex Rosenberg.

In the audience, the real Alex Rosenberg grins.

Marcus Aurelius tells the student that a setback is an opportunity for personal growth. While we cannot control everything, he says, it’s how we react that matters.

Jesus tells the student that his worth is not determined by a job or a title. “My teachings are about finding strength in salvation, not in accumulation,” he says.

Alex Rosenberg says that billions of years of evolution have resulted in humans with uniquely adept brains, so he should use his. Rational analysis will help him find a way forward. Also, he adds, “There is no evidence for the existence of God.”

“I’m right here, bro,” Jesus says.

At the end of the dialogue, the student is filled with renewed confidence, thanks to the wisdom of his three interlocutors.

“I’m free to carve my own path, journeying towards a life that’s rich in meaning,” he says, “where success is measured in wisdom gained and relationships nurtured, and contributions made to the world.”

But, lest this get too inspirational, the students can’t resist one more quip — a dig at Duke’s finance- and status-obsessed culture.

“In the end,” he says, “there’s always Morgan Stanley.”

“One of the things we want them to do is play with ideas,” Jed Atkins said, smiling.

Atkins is E. Blake Byrne Associate Professor of Classical Studies at Duke. He began teaching “The Good Life” three years ago as part of the Transformative Ideas program, which is based in Duke’s Trinity College of Arts & Sciences and supported by The Purpose Project at Duke, a collaboration between the Kenan Institute for Ethics, the Office of Undergraduate Education, and Duke Divinity School. Specifically for sophomores, Transformative Ideas offers students a space to explore deep, enduring questions about the human condition.

“Where, on Duke’s campus, do you go to to ask big questions about meaning, value, and purpose, and to share different perspectives from some of the world’s great religious and philosophical traditions?” Atkins said, repeating a question he’d asked his students.

He found that, all too often, their response was “Nowhere.”

“So that’s exactly why I created the class: to provide a space for students to be able to consider a number of different possibilities for living the good life,” Atkins said. “I think that’s the part of the class that has resonated with students the most.”

Atkins said that he was inspired to team-teach “The Good Life” because of his relationships with faculty members who live according to different traditions. He also had reason to think that students would be receptive to it: he’d been struck by a comment from a colleague who’d observed that members of the clergy, like Imam Abdullah Antepli, were the most popular guest speakers in his FOCUS cluster. While these speakers respected the diversity of beliefs and backgrounds at Duke, he said, they also acknowledged “the hunger for meaning that students have.”

When it comes to meaning, “The Good Life” provides a feast. With the help of other faculty from Philosophy, Religious Studies, Divinity, and other Duke departments and schools, Atkins bring in perspectives from Confucianism to Islam, from Buddhism to scientific rationalism, from utilitarianism to Christianity — then puts them all in dialogue with each other.

“These different traditions have long histories of trying to grapple with these deeply human questions that we all share,” he said.

By exploring these questions together, Atkins finds, people get to know each other in a more profound way. “When you’re engaging in things that are deeply human, there’s a sense of connection that you begin to have with one another,” he said.

The course intentionally fosters that sense of connection between students. Early in the semester, just as classes are getting into full swing, students go on a two-day retreat to Black Mountain, where they share communal meals and participate in activities like archery, rock climbing, and water sports.

“I personally expressed hesitance about going on this trip,” said Bianca Ingram T’25, who took the course last fall. “It’s like, ‘Oh, how am I supposed to go away for a weekend? I have so much work to do.’”

Atkins said this is why he assigns a reading from Marcus Aurelius on the importance of leisure before the trip.

“I always get a couple of students who say, ‘We can’t afford to do that. Everybody else is working so hard. We have responsibilities,’” Atkins said. “And I say, ‘Well, this person was the Emperor of Rome.’ I mean, if you want to talk about responsibilities…right?”

Taking students off campus for a tech-free weekend, while logistically difficult, is one of the best ways Atkins has found to create a community culture in the class. Students seem to agree.

“You know, people ended up talking to me that weekend in ways that I don’t think people from my generation normally do,” said Ingram. “Like, I’d just be sitting around reading, and someone would come up to me and say, ‘Hey, what are you reading?’ And then we’d start talking about the book I was reading and getting to know one another.”

Ingram enjoyed the course so much that she applied to become a discussion group leader the following fall. Instead of TAs, former “Good Life” students lead the course’s discussion sections in campus residence halls, according to guidelines provided by Atkins.

For Ingram, the most important part of the job was creating a space where students are comfortable sharing their viewpoints.

‘Sometimes we might have a very contentious question, like, ‘Oh, do you think fate exists?’ that everyone might be scared to disagree about,” she said. “And then I, as the instructor, have to kind of provoke them and be like, ‘Oh, like, does everyone really agree?’ And you know, assure them that it’s okay to dissent. And by dissenting you add value to this space, because you’re widening the amount of ideas in the room.”

Atkins said that one of the key intellectual virtues he hopes students will develop through these discussion groups is “charity.” By this, he means the willingness to see another person and their argument — “especially if it’s an argument that might make you angry at first” — in the best possible light.

“This is the class where we talk about a lot of things that you’re not supposed to talk about at Thanksgiving, right?” he joked. But while politics and religion are hard to talk about, he said, “we talk about them because they’re important.”

The discussion groups are small, and meet 10 times over the course of the semester, so “you really get to know these students in your group, and you can feel safe with them,” Atkins said. “You can feel that this is a place where I can trust the people around me.”

This trust creates the conditions for risk-adverse Duke students to be a bit more brave. Maybe they’ll feel more comfortable sharing their beliefs, even if others might disagree with them. Or maybe’ll they open up to a new perspective that they’d have otherwise shut down.

And maybe the dialogues, which they write and perform with their discussion groups, becomes a place to forget about achievement, however temporarily, and just play with ideas.

Duke students sometimes “take themselves a little too seriously, and are afraid to get silly,” Ingram said. “But I think one part of education is that it can be fun.”