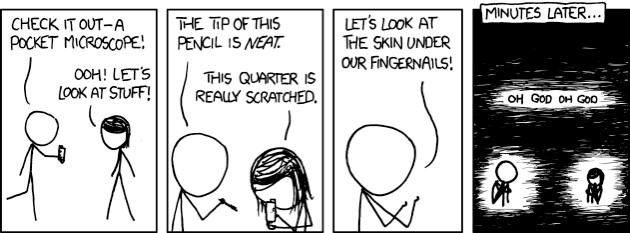

Time to Flip the microscope, class!

While studying abroad last fall a friend expressed “there are so many people eager to study human rights and say they want to stop violations, but they never look at the US!!”

While studying abroad last fall a friend expressed “there are so many people eager to study human rights and say they want to stop violations, but they never look at the US!!”

We were Americans (that is, from the United States) in Amman, Jordan studying geopolitics and human rights – the quintessential ‘American abroad’ topics. After a day of passionate debate over the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Israel/Palestine and de facto apartheid state created by the Israeli government, my friend felt our 95% white cohort spoke hypocritically.

In the moment, I thought my friend was right…BUT. I had a “but.” I thought it fair that our classmates (myself included) have international interests, and okay that our focus was, broadly, abroad. I thought – “We can’t do it all!”

This conversation came to mind randomly over the past few months, but I can’t say my perspective moved much. That is, until this week.

This week I started working on a new project. The project’s aim is a growing one in the word of social and corporate responsibility. Specifically, this growing theme works with renewables companies to expand on their environmental impacts, and investigate potential social and human rights risks, with the hopes of mitigating them.

Not only are more environmentally conscious companies realizing that environmental due diligence doesn’t equate to human rights due diligence, but after the past two weeks’ reckoning on racial justice in the US, more companies are beginning to realize that human rights aren’t just something that need to be accounted for in their ‘abroad’ context.

As I’ve taken the time to do some independent reading about companies’ recent histories in focusing on human rights abroad and failing to turn the microscope inward, terms like “missionary work,” “white man’s burden,” and “colonialism” popped to mind.

I need to be clear; I don’t think organizations in the corporate responsibility field are doing missionary work, nor do I think they’re colonialist, BUT (again, but) I believe the trend to look for human rights abuses abroad is one that engulfs many and is at times dangerous.

To be honest, over the course of my time at Duke I’ve taken only one course that explicitly studied the grossly long, deep, and violent history/reality of racism in America. Much of what I learned shocked me in the same way “Israel/Palestine”, a course I took my first semester at Duke, shocked me.

Absolutely, my basic privilege of being shocked by systems of violence and discrimination that are not only historic, but very present, is something I endeavor to acknowledge and actively combat. However, these past few weeks especially, I’ve come to really recognize that I can’t put these two instances of “shock” in the same category.

Both are horrific. Both are systemic. Both are based in racist ideologies used to control land, people, and wield power.

BUT in relation to the daily life I lead, the systems I uphold, and the systems from which I benefit, only one of these crises exists in my home country.

Only one exists in the country where generations of my family lived. Only one exists in the country where I went to a “neighborhood” public school. Only one exists in the country where black women are four times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related complications like my mother had. Only one exists where black friends and family are five times more likely than me to be incarcerated in a system where black people make up more than a third of prison populations, but less than a sixth of the population.

The list is long.

Not to veer too off-track, but I believe it’s wrong to solely focus on the dangers of being black in America. That is, despite the racist policies that keep so many black people from the voting polls, securing jobs, receiving a quality public education, having a fair trial, and simply living as long as their white counterparts. (In 2018, the life expectancy of black males was 69.1 years, compared to 78.7 white men’s 78.7. For women, black women were expected to live 76.2 years, while white women were expected to live 81.1 years).

That’s to say that black people in America don’t exist as the victims and survivors of our country’s racist policies and citizens’ racist violence. Rather, we as white citizens of the US who are bound by our shared benefit from, continuation of, and complacency in racism. It is our whiteness that creates, spreads, and spurs racism. Not blackness. This is something we must fight within our own whiteness. It can’t be eradicated from outside.

Does this mean I’m abandoning my interest in international relations and fighting human rights abuses in other countries? No. As an American, is it useful for me to go abroad to ‘help’ where my country created humanitarian crises? Is that my responsibility, my privilege, or a righteous want – the white woman’s burden? That’s a conversation for a later blog post.

Regardless, my friend was right.

I’ve seen a tendency both within myself and my ‘internationally-oriented’ peers to believe that if we’re fighting some kind of human rights abuses—whether that be in our home countries or abroad—then we’re doing our due diligence. “We’re playing our part in creating a safer, more just, world.

*Read dramatically* “We’ve done enough.” *Puts hand to forehead*

Now, I don’t think that’s true. As loudly as I’ll debate the existence, use, and implications of borders, they create the microcosms of life within our shared world. They cordon us off and protect us from some actions beyond them, but they also carve us in. They delineate a swath of land on which we not only live, but share.

As long as we’re living, sharing, and benefiting from inequalities that run within our borders, to look only abroad is not only wrong, but dangerous.