In May 2019, the Rights Writers discussed what perspectives have been left out of the major debates on their topics and how including them increase understanding or contribute to progress of the issue.

Last week, lonely and drowning in homework, I went home. Not to my home – plane tickets to Wisconsin are expensive, so I haven’t flown back since Christmas break – but about 20 minutes off campus, to a little one-story ranch which reminded me of the houses on the street where I grew up. This was a required visit to check up on my mentee in the Kenan Institute’s SuWA program, which pairs female Duke students with immigrant women to foster English skills, but as I walked through her door, I felt instantly at peace. I had expected to stay maybe an hour, ensuring the living situation met my mentee’s needs and perhaps filling out some paperwork. Instead, as sunset streaked the sky, I sat eating Jordan almonds on my mentee’s back porch and playing with her sister’s baby. We talked about her own time at university (she found her pharmaceuticals degree fascinating and wishes she could use it in America), her love for The Addams Family and poetry, and her willingness to get any job at all to keep busy and help provide for her family. By now, it had been almost two hours since I’d arrived, and I had a paper due the next morning; I pulled out my phone to check for nearby Ubers.

But as I did so, her sister’s husband stuck his head out the screen door, inviting me to stay for dinner. It wasn’t a hard decision – with spices wafting out the window and hand-cut fries bubbling in hot oil, I was suddenly ravenous, despite the almonds. We ate pasta and meat, steamed broccoli and brussels sprouts, bread hot from the oven, the fries. Though this wasn’t my own family gathered to dine together, I still felt nourished in body and spirit, temporarily liberated from the frenzy of Duke life. The fat gray cat rubbed against my leg under the table. I felt at home, at peace. Later, riding back to campus, I realized I’d spent over four hours with the family.

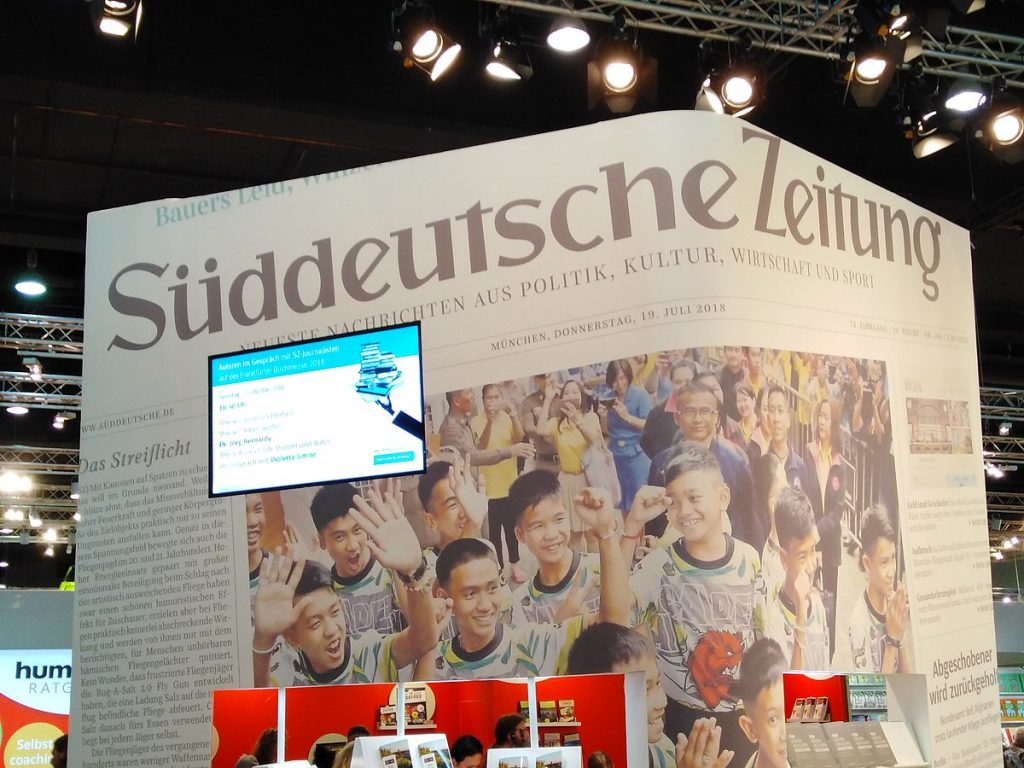

Why do I tell this personal story in my final post as a Rights Writer, when I’ve been writing all semester about the migration stances and statements of people far more globally significant than me, in Germany, a country thousands of miles from my home? For this last prompt which asks me to turn the coin on its head, I wanted to make an example of the sort of rhetoric I believe is vital for us to take up: narratives which bloom from flesh and blood, stories which can acknowledge both trauma and hope, which work in and through lived experience.

We know that stories are more persuasive than pure statistics. Data help us draw comparisons and illustrate the scope of problems, but as the numbers involved grow larger, especially into six and seven figures, our ability to comprehend their true scale evaporates. Although migration policy directly impacts the lives of millions of individual people, each with their own memories, loved ones, and aspirations, politicians’ numerically-centered pronouncements implicitly brand migrants as units in a broader sociopolitical machine. This type of discourse risks convincing citizens that migrants’ only value stems from their economic contributions to society – which are considerable, but, if exclusively focused on, can obscure each individual’s humanity. We must look beyond the financial benefits immigration offers to society to the vital importance of preserving the rights to freedom of expression and safety from physical violence, inalienable to people everywhere.

Christina Boswell, who has consulted for humanitarian organizations including the UNHCR and now teaches politics at the University of Edinburgh, proposes a new model for migration debates. She writes that migrant advocates often perceive xenophobia as stemming exclusively from ignorance and as curable by data demonstrating the contributions migrants make. While this is sometimes true, she argues, immigrants often also become targets for citizens’ existing economic and social anxieties. In this latter case – for instance, when right-wing politicians convince the jobless that their unemployment continues because migrants have “stolen” their positions – progressive parties and the media can help combat xenophobia by amplifying authentic refugee narratives rather than data. Germany has already put this technique to good use, she writes: in the early 2000s, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) slowly overhauled immigration discourse by emphasizing the value skilled immigrants could offer to a 21st-century economy, making possible the liberal migration policy current Chancellor Angela Merkel has championed. Today, rhetoric can serve a crucial role in re-stoking empathy in a debate which risks becoming a tangle of statistics. If every German who supports the far-right Alternative for Germany party could read immigrants’ stories and understand the poverty, violence, and destruction forcing them to leave their homelands and make the lengthy, arduous journey to Europe, they would be far less likely to stereotype and fear the other.

As an eighteen-year-old Duke freshman, I often feel powerless to work for justice in others’ lives. I don’t have a college degree or vast sums of time or money to donate, nor do I have much specific expertise to offer. What I can do, however, is share my experience receiving profound kindness and hospitality from those many Americans never have the chance to interact with. Statistics are valuable and should inform migration policy, but politicians, journalists, and all those who want to change the human heart must focus on the table and the people sitting around it. They must make real for all of us the immigrant women ladling food onto our plates like our own mothers, the babies cooing gently in their high chairs, the love radiating like light through the room.