In doing environmental reporting about vulnerable populations from certain privileged perspectives as a Chinese-American university student, I find that it’s critical to constantly question if I am giving full dignity, voice and worth to every person I interview. None of us—no matter how educated or well meaning—can escape that we grew up in societies where colonization, brutality, capitalism, suffering, inequality and corruption are the norm.

Brave reporters who have questioned this status quo have often ended up in danger. The topics that environmental journalists are investigating involve wealthy, powerful organizations and leaders who are driven by retaining power and profit—retaliating snooping with violence. War and corruption journalists are the first beats that people think are the most dangerous. But, environmental journalists are perhaps even more so on the front lines with frequent investigations into risky stories of resource and animal poaching, corporate practices or various criminal activities—not to mention the physical exposures of being out in the wilderness.

Before he was executed by the Nigerian government for his environmental advocacy, Ken Saro-Wiwa said: “I’ve used my talents as a writer to enable the Ogoni People to confront their tormentors. I was not able to do it as a politician or a businessman. My writing did it …” (Agbo, 2018).

In standing up against the Royal Dutch Shell Company and standing for his people, he was hanged by a military dictatorship. Environmental harm and degradation is violent in every way. When we think about stories of the environment, we tend to want to think about the flowers and rainbows, naively believing that some combination of education and science will bring about environmental justice. From the power structures that dictate whose environment and livelihoods matter to the erasure of entire communities’ land, resources and existence to fuel those in power—manipulation and violence is at the root of the environmental beat.

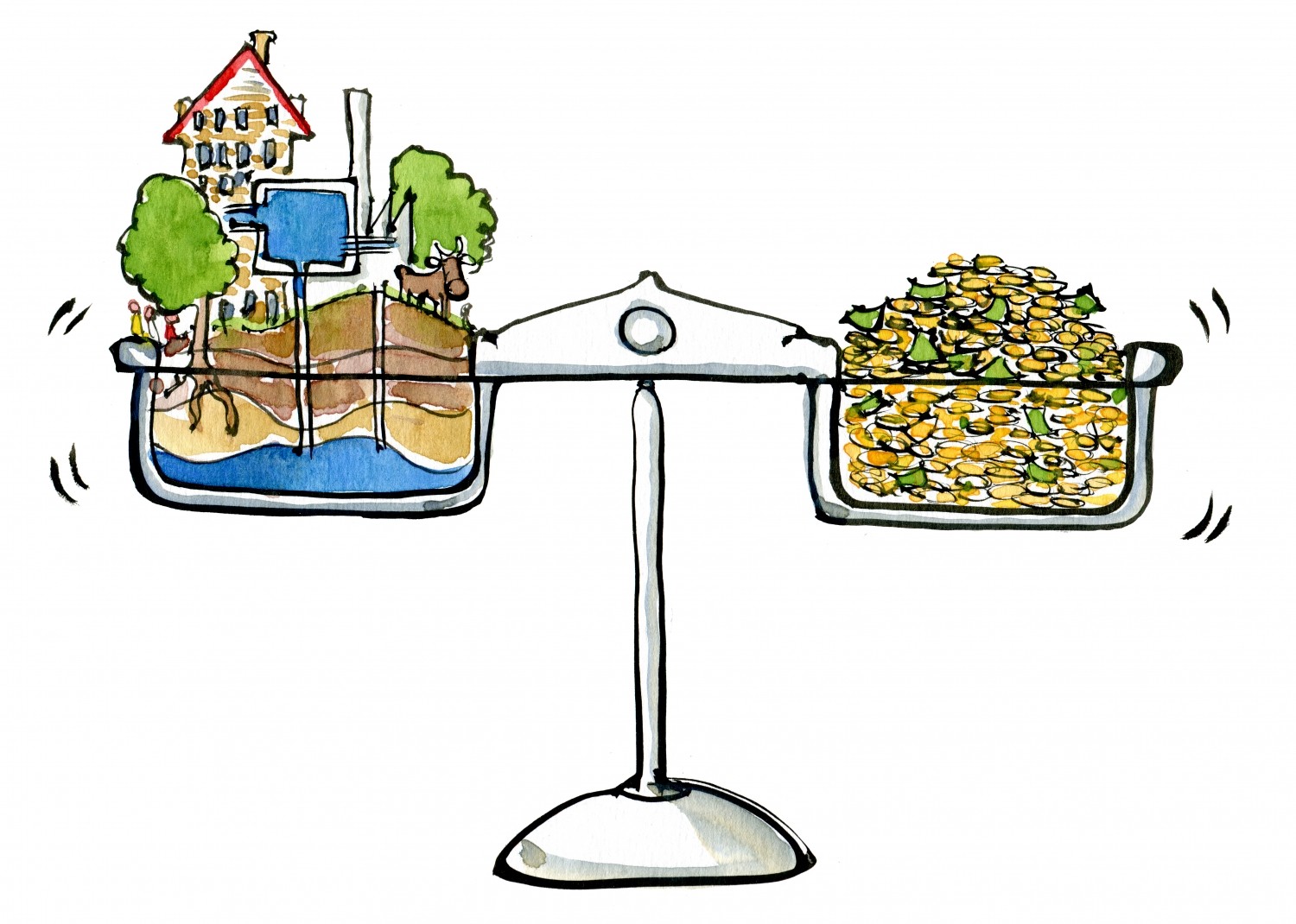

The privilege that most environmental journalists, especially those from wealthy nations, must grapple with is that as much as we want to help prevent exploitation of the environment and advocate for sustainable, ethical usage, we probably don’t actually care as much as we’d believe. It’s likely that the sources that we’re interviewing for many of our stories care and know much more than we do. It’s also likely that our own ways of living directly contribute to the violence that we are shedding light on. For example, I have covered stories of fracking exploration and harm, but I know that I consume far more fracked energy than the people whose livelihoods are being destroyed by the extractives industry.

Outside of mainstream media

What’s interesting about environmental journalism is the relatively greater independence it has from the mainstream media, which covers more international climate change reporting rather than the stories closer to home and is also more easily influenced by powerful interests. Canadian Miles Howe who was working for a small independent online news reported on the protests of gas exploration in New Brunswick where violent arrests were made and “the mainstream media was showing up late or getting it wrong.” In Bhutan, bloggers on the environment like Phuntsho Namgyel were setting much of the dialogue on environmental reports that questioned the government’s stances in a country with strict media censorship. “Bloggers sometimes do the best reporting especially when traditional journalists are silenced,” the handbook says.

Many environmental stories are unreported or underreported which is where innovative NGOs like Oxpeckers and many others step in. The stories that are reported are often ones that many people and organizations don’t want to know about or actively suppress.

In the U.S., there is an intentional effort for environmental journalists, and journalists in general, to distance themselves from activism. As I had the opportunity to do environmental reporting in South Africa and Bhutan, I’ve found that many other nations tend to not worry as much about blurring those lines. From what I have experienced, the line between advocacy and journalism is a privilege that is not necessary for quality reporting.

It’s not about seeing both sides, but about navigating our own biases to tell true stories that lead to accountability. Environmental journalism to me is a way to stand up for the most accurate accounts of truth in stories relating to the environment. It’s not easy or straightforward, but when a journalist sees truth that doesn’t have voice and power, it’s our profession’s responsibility to advocate for those stories.