It’s no coincidence that the person who initially introduced me to the work of Leslie Jamison is now the one with whom I’ve conspired to bring the author to campus next week. About a year and a half ago, thanks to my former professor Duncan Murrell, who directs the writing program at the Center for Documentary Studies, I began seeing mentions of something called The Empathy Exams. I was curious, but wary; it felt as though there’d been a slew of mainstream media reportage of late that broached the topic of empathy, usually producing absolute conclusions—whether to say that “rich people just care less” or “reading literary fiction improves empathy.” The latter take was, and is, especially popular (and especially controversial, insofar as such a topic may be deemed controversial). Around this time, I was very kindly sent an article with a headline reaffirming literature’s empathy-inducing qualities. Next to it I annotated, with a healthy dose of snark, “breaking news!”—both to signal my agreement that, yes, I think reading literature can allow us to better visualize, understand, and therefore care about the lives of others; but also that the undercurrent of so many writings on empathy seemed to prefer, and promise, shortcuts over what we surely must understand by now as the messiness and nuance of human experience. The subjective spaces where we try, and fail, to empathize. The spaces where we promulgate the merits of empathy but cannot give our full attention to another.

And then I read an excerpt, in The Believer, from this forthcoming something called The Empathy Exams, and immediately I knew I felt something different. Here was a writer writing against herself, against her minute actions and her macro-histories. The essay, also called “The Empathy Exams,” is about Jamison’s experience as a medical actor. She writes about getting paid to act out symptoms for medical students to diagnose. She also writes about herself, as Leslie Jamison, about her pregnancy and subsequent abortion at age twenty-five, about her drinking, her boyfriend, her ailments, her loves. About her ability and inability to minister care, and about her expectations to receive it, and frustrations in not receiving it. She interweaves the instructions for her “standardized patient” with an imagined set, for “Leslie Jamison.” She concludes with the latter. An excerpt:

You wake up from another round of anesthesia and they tell you all their burning didn’t burn away the part of your heart that was broken. You come back and find you aren’t alone. You weren’t alone when you were cramping through the night and you’re not alone now. Dave spends every night in the hospital. You want to tell him how disgusting your body feels: your unwashed skin and greasy hair. You want him to listen, for hours if necessary, and feel everything exactly as you feel it—your pair of hearts in such synchronized rhythm any monitor would show it; your pair of hearts playing two crippled bunnies doing whatever they can. There is no end to this fantasy of closeness. Who else is gonna bring you a broken arrow? You want him to break with you. You want him to hurt in a womb he doesn’t have; you want him to admit he can’t hurt that way.

I read these essays one by one in Dublin last summer, upon returning each night to my living space from long interviews with a lot of people I’d never met before. I would catch up on food I hadn’t had time to eat earlier, lie down, and open the book. The combination of these practices just fit. In one of her essays, Jamison visits Texas to attend a gathering of people claiming to suffer from an elusive condition called Morgellons Disease. In another, to support her runner sibling, she attends the Barkley Marathons, an almost unbelievable constellation of treacherous runs through the woods near Wartburg, Tennesse. She travels to Mexicali and consorts with radical poets; she gets punched in the face in Nicaragua; she slips into a “gang tour” in Los Angeles; she writes about stereotypes of “wounded women.” In these essays Jamison doesn’t prescribe or moralize; her voice undulates across the circumstances in which she both plants herself and finds herself. She creates space by exposing the connections between events, texts, relationships, assaults, proclamations of guilt and innocence. This is the writing of someone who moves through the motions by refusing to move forward until she works out why and how she enters these motions in the first place. In her own words:

Empathy isn’t just something that happens to us—a meteor shower of synapses firing across the brain—it’s also a choice we make: to pay attention, to extend ourselves. It’s made of exertion, that dowdier cousin of impulse. Sometimes we care for another because we know we should, or because it’s asked for, but this doesn’t make our caring hollow. The act of choosing simply means we’ve committed ourselves to a set of behaviors greater than the sum of our individual inclinations: I will listen to his sadness, even when I’m deep in my own. To say “going through the motions”—this isn’t reduction so much as acknowledgment of the effort—the labor, the motions, the dance—of getting inside another person’s state of heart or mind.

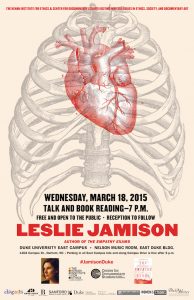

Jamison visits Duke on March 18 and 19 (she will give a public reading on Wednesday, the 18). It’s funny—this post began as a mechanism to link to some samples of her work for those who might be interested (speaking of, you can find lots more here, here, and a nice interview here). It evolved into my own re-reading of some of her work, and an emotional weightiness, and charge, in feeling myself identify. And that feeling—or my moving through the motions of it—gave rise to more questions. This is, I think, the bare motion prompted by experiencing material—be it artistic, scientific, spiritual, or perhaps all three—that is powerful, worthwhile, and unique.

—MD