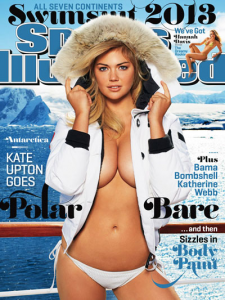

I am not the resident expert on sexy, sex, sex, but recently, I stumbled upon a Sports Illustrated cover that caught my eye:

I am not the resident expert on sexy, sex, sex, but recently, I stumbled upon a Sports Illustrated cover that caught my eye:

In an effort to be innovative (because the bikinis couldn’t get any skimpier), SI decided to tour all 7 continents for its swimsuit edition. The model on the cover, Kate Upton, had the pleasure of shooting in Antarctica.

Yes, Antarctica.

For those of us who have ever braved the cold in clubbing attire, we understand the sheer agony of this feat, and we don 40% more coverage (at least I would hope).

Kate Upton modeled outside, in temperatures around -18 degrees Fahrenheit for 6 days. According to Upton, as she stood naked on set, she “literally couldn’t move, and the editors had to pick up [her] legs and put [her] into the next outfit.” After Upton’s grueling shoot, she suffered bouts of blindness and deafness, symptoms of hypothermia.

Despite this horrible ordeal, SI remains smug and Upton thankful for her opportunity. In the industry, when a model harms herself on set, she is accountable for taking the job. So instead of filing a lawsuit, Upton is thanking her lucky stars that she has recovered and her frozen beauty has launched her career to meteoric heights.

But, is this fair? Did Upton freely choose to compromise her health in order to appear on the cover of SI?

Given the cut-throat nature of the modeling industry, both models and employers understand a fundamental truth: there is little demand for bettering models’ working conditions. If Kate Upton refused SI’s offer, there would have easily been 10, if not 100 girls who would have jumped at the offer. Models are dispensable. Career-defining opportunities are not.

This psychology has long-fueled the industry’s battle with body image and eating disorders.

In 2006, Brazilian supermodel Ana Carolina died from “complications from anorexia” after being told two years earlier that she needed to lose weight.

In 2007, supermodel sisters Eliana and Luisel Ramos died within weeks of each other from “malnutrition and starvation.” Their agency blamed this on an “obvious” genetic disorder.

In 2010, French model and actress, Isabelle Caro, passed away. Her shocking and emaciated body was shown as a campaign against anorexia.

At some point, we have to ask ourselves, how much is too much? How edgy is too edgy? How thin is too thin? Recently, fashion houses in Spain and Italy imposed a BMI limit on models to discourage anorexia. This is certainly a step in the right direction, but it is not the end-all-be-all. We need more productive discussion on fashion, image, culture, and working conditions for models.

Bethany asked in an earlier post whether we have an ethical obligation to stop watching football. I ask, do you feel the moral obligation to stop subscribing to SI? To stop patronizing fashion brands which project an unhealthy body image?

I wonder, what ethical responsibilities to models have? Recently, some fashion models have banded together to form the Model Alliance and drafted a models’ bill of rights. Should new superstars like Kate Upton leverage their influence to lend solidarity to young models?

Given National Eating Disorder Awareness week at Duke, it is time to examine our collective supply and demand that fuels the industry.

On April 21, 2009, the Onion posted a spoof about U.S employees outsourcing their jobs to workers in developing nations:

On April 21, 2009, the Onion posted a spoof about U.S employees outsourcing their jobs to workers in developing nations: