After several months away, Kenan’s finally headed back to our home base, the West Duke building. Keep track of the move on our Instagram (@KenanEthics).

After several months away, Kenan’s finally headed back to our home base, the West Duke building. Keep track of the move on our Instagram (@KenanEthics).

Ellerbe Creek is a body of water that runs through downtown Durham. Meaning: it runs through our city and contains our muck. “Think of all the medicines people take and then flush down the toilet,” the tour guide implores. “I wouldn’t let my kids swim in here. Fecal coliform.”

The water looks mucky indeed: clay-colored, churning fast, loopy with oily bubbles. It feeds into Falls Lake, which is not a natural lake. Its non-naturalness frustrated, and continues to frustrate, nearby residents; their land was taken and dug and filled with water, yes, but also mosquitoes and pollution.

The tour of the Glennstone Nature Preserve turns out to be as much about the surrounding forest—its canopies, its rose-hips and big-bodied black snakes, its spray-painted neon orange, marking where public land stops and Army Corps land begins—as about the water itself. (Where did my body end and the crystal and white world begin?). It is also, perhaps equally, about the history of Durham development, filtered through two Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association tour guides. They’ve lived in Durham long enough to have conversations with people who worked in Erwin Mill when it was an actual mill. Blue jean indigo used to run into the creek.

I scribbled that in my notebook the other day—the creek running blue—because I liked the image (forget the pollution!). But my assignment, assigned on the creekbank, was to write about something I’d noticed on the trail, and to describe it in formal, third-person detail. This was—is—hard for me. I wanted to write about the two women tour guides, how they gave our group a collaborative map of Ellerbe Creek by finishing each other’s sentences. How their excitement about stump sprouts excited me. How the leaves looked next to the mushroom fairy rings. I wanted to understand the forest, the creek, and the developed land holistically: one thing, albeit nuanced, but one thing. I wanna be cohesive!, as the fictional Hushpuppy moans in Beasts of the Southern Wild.

In other words, I wanted to position myself at the center of the ecosystem: me, writing about my surroundings. Which is funny, because I’d just dropped in on this trail on this day through a writing class I’m taking. And as I told one of the guides, I’d lived here my whole life, but never traversed the banks of Ellerbe. 23 years is a lot of time for a city to transform: livelihoods can revert, invert, take different shape. So can creekbeds and the creeks they carry.

It’s a lot to ask to understand the before, during, and after—of a place, a person, a story. On this day, September 11, I read a Facebook remembrance post by a friend. She wrote about those of us who have little memory of what came “before” that date. I was in fifth-grade; I’ve recounted “my” story a million times (it was sunny out; I was confused about how something bad could be happening in the world if it was sunny out). But it was vaguely kid-stuff before, and adolescence after.

I start to wonder: is that before memory within my control? What about the during, and after? I asked one of the tour guides if an investigative article had ever been written about Ellerbe, considering the creek exists within plain sight of Durham’s residents. “No,” she said, after asking her tour partner. “Maybe you should write it!” I fantasized my potential agency: I write a luxurious, sprawling journalistic account of the creek’s history, and suddenly more people care. It’s the same fantasy that flickers sometimes about my project in Dublin this summer: if I write a good piece about the multiple dimensions of The Exchange’s suspension, maybe more people will care that it happened at all, or at least want to understand the situation more deeply. Maybe they’ll want to understand each other more deeply.

I start to wonder: is that before memory within my control? What about the during, and after? I asked one of the tour guides if an investigative article had ever been written about Ellerbe, considering the creek exists within plain sight of Durham’s residents. “No,” she said, after asking her tour partner. “Maybe you should write it!” I fantasized my potential agency: I write a luxurious, sprawling journalistic account of the creek’s history, and suddenly more people care. It’s the same fantasy that flickers sometimes about my project in Dublin this summer: if I write a good piece about the multiple dimensions of The Exchange’s suspension, maybe more people will care that it happened at all, or at least want to understand the situation more deeply. Maybe they’ll want to understand each other more deeply.

In this current, there’s an ethics of control, and there’s an ethics of empathy, and I want to be able to cite enough philosophers and enough theorists to cover every inch of nuance of both. I’m not sure that project is within my control, nor am I sure it should be. Inevitably, it will revert, invert, take different shape.

This morning, feeling weight from the day and from the idea of writing, I walked outside our building and sat at a picnic table and watched a ball of fluff float until my eyes strained or the ball became indistinguishable from the color of the sky or both. I sat there for a few minutes and then walked back. My legs lately feel taut and Tinman-like. (I just started dancing again after a few months’ break. “I’m a little rickety,” I keep telling people. I also walked about 1.6 miles through the woods yesterday).

I came inside and opened The Chronicle; there was a 9/11 Remembrance advertisement on one page, and a giant Miró painting on the other. I came back to my desk, and Ikea USA had tweeted, “Save time for reflection this Patriot Day morning.” (The account has since deleted the tweet). I felt strange about that (who decided it was called “Patriot Day,” anyway?), so I started writing my way into and out of it—that current, that stream—controlling only as much as the words ahead of me.

—MD

By Michaela Dwyer

This past Sunday I tweeted, “note: don’t wear Keds to a rally.” It was “favorited” (that benevolent form of Twitter approval) in quick succession by three friends.

The previous day—and the night previous to that—I’d spent much of my time mind-circling around the proper attire for Saturday’s Moral March on Raleigh/HKonJ. I felt like I was preparing for a dance performance or field trip, much like the over-conscientious grade-schooler I once was. Then and now, my mother had ensured I had a bevy of warm jackets at my disposal. Also heavy-duty winter gloves. (I have Raynaud’s, so cold-weather outings quickly feel like an assault on my extremities—if numbness can be classified as an assault.) But I couldn’t decide on shoes: would the mood be rowdy, and would, in turn, nicer boots get scuffed? Would more sturdy hiking shoes prevent me from wearing the style of coat in which I felt most comfortable, most myself? What image did I want to present of myself to the other ralliers and would that image align with maximum body heat?

As I paced around my room considering outerwear and shoes, I realized I was treading a deeper insecurity about the next day. At the march, what would happen? Presumably, thousands of people from around North Carolina and elsewhere would walk a few blocks toward the State Capitol in downtown Raleigh. People would speak. There would be banners and flyers. There would, as online information claimed, be no civil disobedience—en contra to the Moral Monday protests that took place over the summer last year.

But what about the number of possible negative happenings that those bare-bones probablies don’t include? Violence—physical or otherwise—against the marchers, provoked by the sheer number of people gathering en masse? Overcrowding? Counter-protests? A pandering pile of cookies left out by our governor ? Promises of more of the legislation we were rallying against? Cold fingers and toes?

**

The DukeImmerse students and I have lately been reading a book of “anthropological philosophy” called Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. The author, Jonathan Lear, profiles the Crow Nation just before their confinement to reservations, and how such confinement devastated Crow culture as tribe members knew it. A statement by Plenty Coups, the last great Chief of the Crow Nation, propels Lear’s investigation: “When the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground. And they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened.”

Lear writes at length about what he thinks Plenty Coups means by such a pronouncement: After the traditional Crow culture is rendered non-functional by the introduction of a new culture and way of life (the reservation), things couldn’t “happen” in the same, or even remotely similar, ways that they used to.

At least partly to cut through my chronic fear of the unknown, I’ve been thinking about what it means for something to “happen” in the first place. Recently I feel as though I’m regularly bombarded by news about bad things happening: someone I’m close to being diagnosed with a serious illness, the perpetuation of statewide policies that I feel violate my rights as a woman, supporter of public education, voter, human, et al. My job at Kenan quite naturally brings me into contact—however physically removed—with issues facing communities worldwide that could be categorized as “heavy” and “complex.” It is both a privilege and an overwhelming task to sit, reflect, and write on these various happenings each week, to tidy and term them, at least for my mind’s own sake, under “ethics,” when I know that my contribution is not immediate and that these occurrences lie largely beyond the power of my outstretched arm.

**

On Saturday, that arm ended up bundled in a meager sweatshirt. I chose to cover my core with a down vest I haven’t worn since high school, and the two friends I drove to the rally poked fun at me (“nice vest!”) in the same way one might “favorite” a tweet. Underneath was a sweatshirt emblazoned in Helvetica with the words “Support Your Local Artist”; I thought the statement mildly appropriate for the event. I found the sweatshirt, discarded, while working for a state-funded program at Meredith College last summer, when Moral Mondays were hot, literally and figuratively, and I presided over teenagers while many of my peers marched a few miles down Hillsborough Street. I imagine that the bulk of those peers, and also several of those teenagers, were at the march this past Saturday. I didn’t see many of them, but I was at the back of the crowd and had no real sense of its size. It turns out there may have been 100,000 people there. Among them were more Duke undergraduates than I’ve seen at any off-campus event besides designated bar nights in downtown Durham.

Last fall, a friend, mentor, and former teacher wrote the piece I’d like to write about why I had to at some point stop imagining the rally into a negative realm, or at least straddle that fear while standing, flimsy Keds laced, among an enormously calm, ethnically and generationally diverse group early Saturday morning. He writes,

“The Legislature has made clear that it’s time to pick sides. The human instinct is to hope that this too shall pass, but this is no longer operative. We want to think bad things are just temporary and that eventually right-minded people (to be named later, but people with more strength and greater resources) will put this thing right. We want to believe this because we want to believe that the universe is essentially just.

But things do not just pass. And while we’re waiting, things are being done that can’t be undone.”

I think back to Plenty Coups. “When the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground. And they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened.” Our (because it is our) North Carolinian predicament is far different, our contextual narrative far from that of a singular devastation. But we’ve internalized pieces of a similar threat as it pertains to us today. Laws and policies, especially those that come to counter the ways in which many of us live or want to live our daily lives, are peculiar at best and obliterating at worst in their power to ride along with our habits one day and invalidate them the next. After this nothing happened. It’s hard to think of our habits as something we actively create, as what’s happening, especially when it’s laws, policies, and major [largely negative] events that make the news. It’s radical to imagine that our quotidian experience matters on the large-scale. It’s radical to gather with tens to hundreds of thousands of people to attach bodies, signs, and a march to that imagination.

And it felt radical, on Saturday, to be a part of that happening. To say yes, we are able, and we are making this happen right now.

By Michaela Dwyer

I have struggled to start this post because it feels impossible to write a photograph.

Somewhere, sometime, it was once said—or at least written down—that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” When I worked on Recess as an undergrad, my fellow writers and editors volleyed this unsourced quotation back and forth repeatedly—or at least when we were feeling contemplative about our endeavors, our responsibilities as budding cultural critics. How do you write about music if, when you boil it down, it’s just two mediums rubbing against each other? How do you explain dance without moving your body? How can you know what it means to be another person without, by some magic empathy potion, transmogrifying into said other human being?

A few days ago I sat with the DukeImmerse: Uprooted/Rerouted students as they discussed a photography and writing assignment they’d done over the weekend. Since winter break they’ve been training themselves in the type of fieldwork around which their curriculum and experience this semester is built. In little over a week, the twelve students will split up and travel through mid-March to Nepal and Jordan, respectively, to conduct life-story interviews with refugees. These interviews are, of course, with people the students have never met before; they can take place for anywhere between two and eight hours; they aim to collect data about the qualitative experience of displacement. None of the students have previously visited either country. And, for many, this semester marks their entry-point into the political, cultural, medical and ethical issues experienced by refugees and displaced peoples worldwide. On day one of Field Ethics class, program director Suzanne Shanahan told the students they were, at Duke and in Durham, “already in the field.” This proclamation was met with serious faces and ambivalent giggles. I wrote in my notes, next to a sloppy Venn Diagram (“engagement” in one circle, “field research” in the other, and “ethics” in the overlapping space between): “WE ARE IN THE FIELD ALREADY.”

How to be in a field we already know so well? How to dance about architecture? How to talk about anything at all? Sometimes I experience an anxiety so debilitating that I can’t “start” in the first place. It’s the fear embedded in the prospect of doing things wrong, of not properly conveying the nuance and complexity that propel us to talk, document, relate in the first place. When setting off to do interviews with refugees, the ethical stakes amplify intensely. These are people whose livelihoods have been placed at the whim of political decisions beyond their control, who have been shuffled en masse and categorized and quantitatively researched but perhaps infrequently asked how they feel—physically, emotionally, spiritually, mentally—when any of that happens.

I take a quick inventory of the number of people I can rely on to ask me how I feel on a regular basis, who can translate a facial expression to ameliorating conversation, or a movie suggestion, or an internet link to a painting that person thinks I’d like. I think about how my structures of comfort are quite complex and deep, and about how my memories of the spaces I’ve inhabited for the 22.5 years of my life thus far are accessible and re-inhabitable by a short car ride. I think about my basic freedom to advocate and assemble, in this country, for things I feel are right and wrong, and the possibility—which I must believe will always be a possibility— to push these feelings toward policy. I say all this not to render a contrived comparison of my life to that of a refugee, nor to superficially enumerate my privilege; the latter, especially, feels to me a project far too continuous and nuanced to try to put down in a pithy sentence on paper (or, the web). The former overwhelms me in its crudeness. I envision a Venn Diagram: me on one side, a Bhutanese refugee woman my age on the other. In the middle are our similarities, bullet-pointed and double-spaced. I shudder at the idea that this exercise could bear a hint of our essences or idiosyncrasies, a slice of something akin to the “truth” of each of us as human beings living in the world in 2014. And, of course, for whom do we bear this information? Data-collecting agencies? Governments demarcating cartographies that further restrict the movement of populations, communities, individuals?

But then, in class, we look at one photograph taken by one student in fulfillment of a field photography exercise investigating instances of “joy.” The photo is framed by a closed car window, and in the center of the image, a multi-colored moth perches on the side of a palm. A ray of sun hits it right on the wing and for a second everything is illuminated—the way the photographer sees emotions, the connection between animate and inanimate things. The class discusses. It seems important, they note, that this particular photographer and subject may not necessarily attach “joy” to a smiling human face. It seems plausible, they note, that this mini-exercise could resemble a way to attune to cultural differences “in the field.” We move to the next photo to compare (and contrast).

We are in the field always because we need to know where we come from in order to grow an analytic imagination. This is the imagination that allows us to understand that there are people besides ourselves in the world who are doing exactly the same—feeling things, remembering events and emotions, and documenting them according to their own metrics. How overwhelming to embark on this complexity, and how seemingly difficult to find the answers. But, if anything, the answer must be in the [field] attempt.

By Michaela Dwyer

“The Support Group, of course, was depressing as hell. It met every Wednesday in the basement of a stone-walled Episcopal church shaped like a cross. We all sat in a circle right in the middle of the cross, where the two boards would have met, where the heart of Jesus would have been.

So here’s how it went in God’s heart: The six or seven or ten of us walked/wheeled in, grazed at a decrepit selection of cookies and lemonade, sat down in the Circle of Trust, and listened to [Support Group Leader] Patrick recount for the thousandth time his depressingly miserable life story…

Then we introduced ourselves: Name. Age. Diagnosis. And how we’re doing today. I’m Hazel, I’d say when they’d get to me. Sixteen. Thyroid originally but with an impressive and long-settled colony in my lungs. And I’m doing okay.”

These are the words of Hazel Grace Lancaster, via John Green, describing for the first several pages of The Fault in Our Stars the cancer support group she is newly required to attend (reasons: isolation, depression—the latter of which she calls, like everything else, including cancer, “a side effect of dying”). Hazel’s (and Green’s) narrative voice is clear from the start: she tells it—her world—like it is to her, sans airbrushing or sentimentality. She is skeptical in a quintessentially teenager-y way, but she is not unempathetic (even with the somewhat ridiculous Patrick). She understands the function of the Support Group, the organization of individuals and their connections to each other; she knows that their experience of cancer is shared, albeit not homogeneous. The group assembled in the “Literal Heart of Jesus,” as Hazel begins to cheekily refer to it, produces the characters we (and Hazel) gradually get to know and, against its “depressing as hell” odds, it serves as an important setting for several events over the course of the novel.

Hazel would probably shrug and chuckle at my fear of crudeness in using her Support Group as an entry point to talk about Kenan’s new staff-wide ethics book club (for which we read and discussed Green’s novel The Fault in Our Stars this past Monday). The differences here are obvious: the Kenan book club is not, ostensibly, a support group, and certainly not one oriented around an illness (or books “about” illness). And Hazel, of course, is not a real person—as Green makes plenty clear on his website’s FAQ page [1] for The Fault in Our Stars, as well as his author’s note: “Neither novels nor their readers benefit from attempts to divine whether any facts hide inside a story. Such efforts attack the very idea that made-up stories can matter, which is sort of the foundational assumption of our species. I appreciate your cooperation in this matter.” The delivery of such words feels a little tongue-in-cheek, but I can fully envision Green saying them, as if it’s the most natural sentiment in the world. I can also envision Hazel saying them in a similar tone: undetached, straight-up real-talk, cut from the same humor and nuance that governs our living days (Hazel’s, and all the other characters’, in the novel; ours, in this so-called “real world”).

On Monday, our staff huddled around a conference call with Green and listened to him talk about why he writes books about teenagers, aimed at a teenage audience (thus the category Young Adult, or “YA”). He explained that this was always his intent as a writer, from his early days studying English and Religion and then working as a chaplain in a children’s hospital to now, writing and selling millions of copies of his several books, producing an enormously popular YouTube series with his brother, Hank, and directing a large-scale web-based fundraiser for charities around the world called Project for Awesome. For Green, writing from an adolescent voice feels closest to life itself. “I don’t like to talk about the meaning of life with artifice,” he said. (And neither does Hazel, whose acerbic tone crafts both her and our understanding of her life with cancer, and shuns an over-sentimentalized language of illness. Artifice isn’t really her thing.)

And so the image of all of us—all grown-ups, in a way, or at least all past the age of 21—clutching copies of Green’s book and discussing it with greater openness and emotional engagement than I’ve experienced in many undergraduate English classes felt a little ironic. Adults reading Young Adult literature—this unusual dynamic is something I feel every time I read Rookie, a “website for teenage girls” edited by 17-year-old wunderkind Tavi Gevinson (and one of my favorite sources of reading material online). I regularly devour Rookie’s content much in the way that I devoured Green’s novel. Both seem to move at the same pace life does, both eschew abstraction and pretension (but not quirkiness and intelligence) and are relatable by nature.

A good narrative voice does this regardless of subject matter—but what if the subject matter concerns cancer, and not seductive vampires or high school hallway drama? I hear Hazel once again: well, what if? I doubt Hazel would privilege her particular story over any other one; if you read or have read the book, you’ll see how conscientious she is about trying to reduce what she believes is the harm she—via her disease—inflicts on everyone she’s close to. It’s easy to attribute this philosophy to things like her superior understanding of the gravity of cancer, a burgeoning adolescent self-awareness, or her alignment with realism over romance. But none of these isolated qualities define Hazel, and much like a “real” teenager—or person of any age—her desires and viewpoints shift and expand as the story progresses, and as we see other characters compelled to be close to her. (We’re compelled, too).

And this is not “despite” her cancer, because to say so subtracts an element of her blazing, complex, Literal-Heart-of-Jesus-spunky humanity. The popularity of The Fault in Our Stars is a declaration—from its inception to its immense worldwide readership to our choice to read it for our inaugural book club meeting—that its made-up story matters. The power of this story, and stories like it, lies in its ability to matter, to resonate, to belong differently for and to everyone who reads it—as we learned, in real-time, on Monday, when each of us described our experience of the book with each other and with Green. Getting to know Green’s characters in this novel and then talking about them together felt, in a way, like a step toward visualizing what ethics looks like, or could look like, in everyday life—even, and perhaps especially, when everyday life is greater attuned to our physical circumstances. Part of me (the part of me that chose this book for us to read) feels like YA literature sometimes accesses a fuller vision of everydayness than capital-L “Literature”: or, the books we’re told, as “adults,” best reflect our lives and our concerns. (But, we’ll see—next up is journalist Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity—a recent landmark work of nonfiction, and, I’m predicting, no less complex or immediate.) Either way, being a part of this book club at this point in my life feels like a move toward reclaiming literature that really speaks and sings, regardless of genre or intended age group. And I’m thrilled to keep huddling together each month to do so.

[1] It is my Literal-Heart-of-Jesus-sacred-duty to advise you not read this spoiler page if you have not read, and plan on reading, this novel.

By Michaela Dwyer

The walls in the central hallway of the first floor of West Duke function currently as a gallery. On one, between a long sequence of color photo prints, is a plain text document tacked to the wall, made up of several statements like the following: “It can be a picture of a child burned by napalm running along a highway in South Vietnam. A picture that would turn public opinion on a war thousands of miles away.” At the bottom of the document, these statements are attributed to The Picture: An Associated Press Guide to Good News Photography, published in 1989.

This text—and the photos—are part of Advance for Use Sunday by Caitlin Margaret Kelly, who is both curator of the exhibition “The Icon Industry: The Visual Rhetoric of Human Rights” (in which Advance for Use Sunday is featured) as well as Kenan’s first Graduate Arts Fellow. Kelly came to Duke’s MFA in Experimental and Documentary Arts after a long career as a photojournalist in the U.S. and South America. In a recent Recess article about the exhibition, Kelly credited the shift to her feeling limited by the photojournalism field. She sought out the “ability to pull strengths from photojournalism, from [her] documentary work, from [her] other interests.” Fittingly, the panel gathered on Monday for the opening of “The Icon Industry” reflected this spectrum: journalism (Francesca Dillman Carpentier), documentary (Wesley Hogan), and visual art (Pedro Lasch). Kelly began by asking each panelist to discuss what it means to represent something “well” in their respective fields. Carpentier mentioned a list of rules utilized by journalists to best depict “what’s there”—rules, essentially, for the representation of subjects and/or events deemed newsworthy. I immediately recalled Kelly’s piece. In Advance for Use Sunday, the AP’s “Guide to Good News Photography,” uncannily similar to this set of journalistic “rules,” critiques photojournalism’s traditional standards—and, by extension, the ways in which the media employs iconic images to flatten the public’s understanding of complex events.

After the panel discussion, I chatted with Kelly next to a snack table of cheese cubes. Kelly, whose master’s thesis in visual anthropology examined Vietnam War photographs on the front page of The New York Times between 1962 and 1973, told me that the “picture of a child burned by napalm” was taken, and taken up by the media and the public, rather late into the war, in 1972: a visual coup de grâce for an overseas struggle that, by that point, faced near-universal negative public opinion. In this context, it was the “right” image—a “Good News Photograph,” emphasis on the capital “G.”

But, and as Lasch suggested in the panel, situating this discussion of news images—and I’ll go a step farther and term them “human rights images”—in terms of “good” and “bad” already brings up questions of, as he said, “morality and taste.” These images, once publicized and “rallied around,”[1] become morsels suitable for critical judgment; a critique, in a sense, but too often evaluated only within the framework of the discipline and assignment in which the image came to be. It’s one thing to understand details of the event that produced an iconic image. But, as Hogan pointed out from the documentarian’s perspective, it’s another thing to consider—and take dead-seriously—the photographer’s intent in capturing the image, the circumstances in which the image came to be, the type of relationship between the photographer and his or her “subjects,” the extent of aesthetic control, etc (the list could go on forever). Each of these considerations alters our value-added assessment of an iconic image—or any image, for that matter—and this multiplicity seems the only logical starting point for any discussion, or possible “use,” of such images. But when our culture needs the news, and needs it now, such discussion is quickly shunted in favor of what makes headlines pop and sales go up.

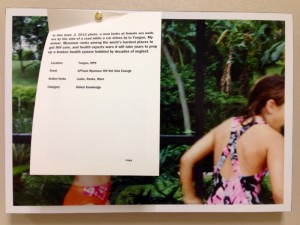

Is such a forum for discussion possible, then? In a way, the panel ended with this question, and we were unleashed to wall-mounted art and refreshments. I spent a while in front of Advance for Use Sunday. If you stop by the exhibition, you’ll see the flippable paper captions atop each photographic print. The exhibited side of each piece of paper provides a condensed description of what’s happening in the photo and categories such as location, event, and action verbs. The large photo to which these captions are attached, however, is immediately discordant. For a description of “a man look[ing] at female sex workers” in Yangon, Myanmar, we see two young white girls chasing each other in apparent playtime glee. The trick is to flip the paper caption: on the other side is the AP image that originally accompanied the AP caption on the front.

The space between these two images is the zone that’s begging to be discussed, to be flipped over constantly, to gnaw on while chewing cheese cubes. It’s an invitation to critical practice in lieu of one-sided critique, and more than anything this exhibition feels like an endless forum for such practice. One of my favorite moments last night was sidling up to Antoine Williams’s enormous painting, characterized by hybrid figures both human and not (it reminded me stylistically of Wangechi Mutu’s collage works, recently exhibited at the Nasher Museum). The person standing next to me turned out to be Williams, the artist, himself. We talked about the painting’s content and his desire to represent race- and gender-based hierarchies in a visually ambiguous way. We “rallied around” his own iconic images for a few minutes, but only in the sense that we immediately got into the thick of the issues Williams wanted to treat in the painting. And then, eventually, we parted, lending our voices to the overall [critical] din of the hallway.

[1] “This rallying around iconic images can be important,” said Kelly. “But to me, the lack of critique afterwards is what the exhibit was trying to start talking about…the lack of understanding that an event or a group of people or a thing is often much more complex than what the iconography shows it to be.” (Recess, Duke Chronicle)