Author Leslie Jamison’s visit to Duke as the second Kenan-CDS Visiting Writer in Ethics, Society, and Documentary Art was a two-day whirlwind that engaged undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, staff, and Triangle community members. Taken on face value, this description would suit just about any campus residency involving a high-profile practitioner, artist, or scholar. But this one felt singular, in a way; as a professor and mentor of mine said, Jamison’s visit, which centered on her much-awarded, lauded, and widely read essay collection The Empathy Exams, “touche[d] so many needs and nerves across campus.” I think this was due, in part, to the issue at the heart of her work—empathy—which prompts (and prompted) such wide-ranging micro and macro reverberations.

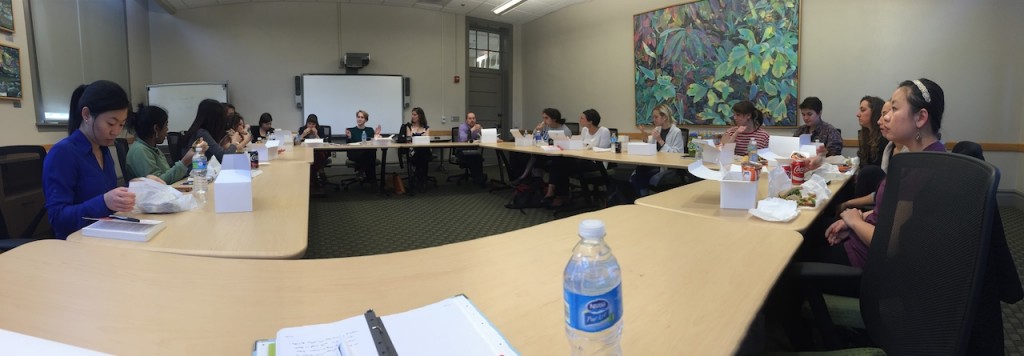

A Team Kenan Do Lunch on Wednesday brought Jamison and 20+ students together to explore questions surrounding the anxiety of expertise in storytelling, gender and writing, and the challenges of crafting a healthy relationship between creative work and everyday living. Staff book club, which convened on Thursday morning with Kenan and Center for Documentary Studies staff members, prompted a lively conversation about the metrics of empathy—When do we give? How do we position ourselves in terms of the needs of others?

Jamison’s panel discussion at the Forum for Scholars and Publics on Thursday, for which she was joined by Jehanne Gheith (Associate Professor of Slavic and Eurasian Studies and MSW), and Lauren Henschel (Duke senior and documentary photographer), was, in one audience member’s words, “awesome, moving, powerful, transformative.” The panel, entitled “Ghost Pain: Caregiving, Documentary, and Radical Empathy,” allowed the trio to share their experiences encountering pain and engendering empathy in their respective practices. Another audience member praised the discussion’s “grounded personal moments of vulnerability.” Their reflections on each others’ work felt electric and connective (and they said as much afterward).

At her public reading on Wednesday night, Jamison read “The Broken Heart of James Agee,” a short essay from a small collection of essays—”Pain Tours II”—within The Empathy Exams (a version of “Agee” was published in The Believer in 2012). About Agee’s infamous Let us Now Praise Famous Men, a 400+-page genre-bending, hulking textual thing that attempts to write about sharecroppers in the Deep South but instead writes about how hard it is to write about, and therefore document, anything, Jamison writes:

Empathy is contagion. Agee wants his words to stay in us as “deepest and most iron anguish and guilt.” They have stayed; they do stay; they catch as splinters, still, in the open, supplicating palms of this essay. If it were possible, Agee claims, he wouldn’t have used words at all: “If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here.” In this way, we are prepared for the four hundred pages of writing that follow. “A piece of the body torn out by the roots,” he continues, “might be more to the point.”

Jamison’s visit was about writing, but it was also, and fundamentally, about so much more. It was about presence: it was about different folks coming out to one or more of her events, and connecting with each other—I had no idea I’d see you here!—and connecting with Jamison in turn (she wrote personal notes in the books of attendees, and they signed her copy of The Empathy Exams). It created a space where global health students met English students; where scholarship became public and personal; where Triangle community members mingled in academic building, talking about what they do, where they work, and how they encountered Jamison’s work. This visit, much like Eula Biss’s in the fall, had a pulse, and that pulse had—has—indentations. Those indentations will live on in our shared conversation, in our shared air—the latter of which, as Jamison said, is as ubiquitous as instances of, and possibilities for, empathy.

—MD