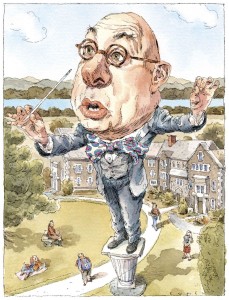

There are several things that interest me about Alice Gregory’s recent New Yorker profile of Bard College president Leon Botstein (the New Yorker paywall is still down, so you can read it here). There’s the objective feat—and perhaps oddity—of Botstein’s 40-year (and counting) leadership of the college, and the fairly young age (27) at which his tenure began. There are Botstein’s intellectual proclivities that position him somewhere between savant and dilettante: he entered college at age 16, did Ph.D. work on the social history of Viennese modernist music, and devotes time to social justice work and orchestra conducting. There’s the institution itself: small, secluded, and aggressively committed to the liberal arts. Extracurricular accoutrements like Greek life and athletics don’t jive there in the way they would at, say, a school like Duke. The types of students Bard tends to attract, Gregory (a Bard alumna) explains, are “easy to caricature.” Instead of “being student-body presidents or varsity point guards, they took black-and-white photographs of their friends’ shoes, wrote first chapters of postmodern novels, and played in noise bands. They were apt to believe that their talents and interests could be assessed only subjectively.”

But the most interesting question the piece arises for me—as a writer, as a reader, and as someone fairly embedded in contemporary higher education— is who, or what, exactly, is being profiled. I left the piece wanting to read at least five more pages of it. I wanted the seedy details of undergraduate life at Bard; I wanted to know what the “parties” Gregory alludes to are like. When I applied to college I was definitely a B&W photo-taker and postmodern novel enthusiast (I didn’t know what “noise” music was until later, when a friend at UNC—who almost went to Bard—explained it to me). Back then, I didn’t know who Botstein was. I didn’t think about the imprints of college presidents on “their” respective institutions, but I nevertheless focused my attention on institutional culture. Did the students at X college care about learning? Did they care about it enough to lay on the grass and talk philosophy into the morning hours? What scenery would I observe from the classroom of my avant-garde poetry seminar? I had the sense that Bard would foster a distinctly different undergraduate experience than a place like Duke. I erred on the side of Duke. And despite that decision’s tie to my sense that Duke and Durham’s relationship was more substantial than that of many New England liberal arts colleges, I still saw colleges as tiny islands. Collectively constructed, but somehow singular in their identities.

Reading about a place like Bard—and about its selfsame leader—does make me think about the college student I could’ve been had I attended elsewhere. But moreso these days it makes me think about what sustainable educational institutions look like in 2014 (and counting). How are their finances managed? Do they have finances in the first place? Do the “eye-catching initiatives” Gregory mentions secure funding, or is it more lucrative to pound the pavement of the traditional liberal arts? Do these initiatives line up with the culture of the student body, and how is that body consciously—or unconsciously—shifting?

I think about Black Mountain College, that remarkable progressive institution nestled in the hills outside of Asheville that attracted an all-star list of 20th century artists and educators. It stayed (financially) alive for only 24 years, from 1933-1957, but the the lore seems to grow bigger with each passing decade. (In fact, the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center just received significant expansion funds). There are books written by alumni with feverish appreciation for their school and time spent there; there are odes to larger-than-life professors and poets; there are odes to being young in the 1940s and happening to attend Black Mountain, and the ensuing magical convergence of these two things. I came across a funny exchange on Twitter in response to Gregory’s article. The respondent suggested that Bard should’ve “followed the route of Black Mountain rather than becoming Botstein University.” Gregory’s response: “Even though Black Mountain doesn’t exist anymore?” Maybe it’s a suggestion that Bard break post-Botstein and, to borrow that modernist adage, “make it new.” Or maybe Bard will cease to exist as the world knows it, as Bard-Botstein are inextricably linked. Then what? The institution—any institution—will look different, but that’s not a passive action. Even as our educational landscape changes, I imagine that learning spaces will subsist: collectively constructed, but somehow singular in their identities.

—MD

You come to West Campus, not for a class or a meeting, but in search of this exhibition—because you want to write about it, which means you want to place it within some larger conversation about the history of Duke and what Duke looks like now. You live and breathe what Duke looks like now, because you both went to school and now work here, so you focus on the visceral particulars. When you get off the bus on West Campus, you’re greeted by heat and negative space. Walking through campus on 97-degree days feels like a whole-body gulp of hot tonic. You take photos of the construction alongside Perkins and the Divinity School; there is no shade, due to the magnolia trees now being gone, but there is the chain-link fence and the excavated dirt behind it. There is the banner on the fake Gothic construction siding: “Coming Soon to Bostock: The Research Commons.” There is the mulch path you must now take to Perkins. A desire line you didn’t make.

You come to West Campus, not for a class or a meeting, but in search of this exhibition—because you want to write about it, which means you want to place it within some larger conversation about the history of Duke and what Duke looks like now. You live and breathe what Duke looks like now, because you both went to school and now work here, so you focus on the visceral particulars. When you get off the bus on West Campus, you’re greeted by heat and negative space. Walking through campus on 97-degree days feels like a whole-body gulp of hot tonic. You take photos of the construction alongside Perkins and the Divinity School; there is no shade, due to the magnolia trees now being gone, but there is the chain-link fence and the excavated dirt behind it. There is the banner on the fake Gothic construction siding: “Coming Soon to Bostock: The Research Commons.” There is the mulch path you must now take to Perkins. A desire line you didn’t make.