Ira Glass took to Twitter recently in an annoyed response to Shakespeare in the Park. “@JohnLithgow as Lear tonight: amazing. Shakespeare: not good. No stakes, not relatable. I think I’m realizing: Shakespeare sucks.” When I first saw Glass’s tweets, I thought he was being sarcastic. Surely he thinks Shakespeare speaks Truth. Besides, Glass is a straight white male, well-educated, a paragon of 20th and 21st century American artistic accomplishment (having originated the popular public radio program This American Life). Shakespeare is part of the canon to which Glass must admit he’s beholden. This is the canon he must in some way relate to, the canon that told him what storytelling was and helped him think about what it could be. After all, as Tom Jokinen proposes in Hazlitt, This American Life’s story structure resembles that of the Bard’s many plays.

Let me back up: This piece—the one I’m writing right now—isn’t really about Shakespeare, or the ways in which T.A.L. is like Shakespeare, or what did Glass really intend when he tweeted those super-mean tweets about Shakespeare? As Jokinen suggests, maybe these are fruitless interpretational impulses, reminiscent of grade-school lessons on Symbolism 101. Interpretation removes us from the personal, tells us that an emotional response (“Shakespeare sucks”) isn’t subject matter for classroom discussion. There’s purpose in this restriction: to characterize the writer’s style, to understand narrative coherence (or incoherence), to distill broad insights about how humans create meaning in life.

But what of the visceral, emotional experience of reading? How do we read? Why do we read? Who is reading? Last week, New Yorker staff writer Rebecca Mead posted “The Scourge of ‘Relatability.’” She criticizes Glass’s knee-jerk “unrelatable” charge. “To demand that a work be ‘relatable,’” she writes, “expresses a[n]… expectation: that the work itself be somehow accommodating to, or reflective of, the experience of the reader or viewer. The reader or viewer remains passive in the face of the book or movie or play: she expects the work to be done for her.” I thought, yes! When reading, when experiencing art of any kind—heck, when living—we should reach outward. Go beyond what we think we know. Be open. Like the final two sentences of Leslie Jamison’s essay collection The Empathy Exams: “I want our hearts to be open. I mean it.”

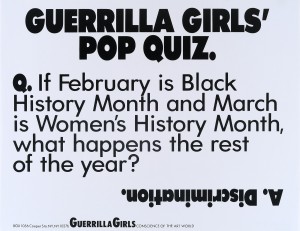

But doesn’t this start by flexing our emotional muscle? Giving ourselves over to the knee-jerk because it’s what we feel first? There’s Ira Glass saying, “Shakespeare sucks,” and then there’s a black teenage woman reading, in English class, book after book authored by white men, detailing the exploits of white people, thinking, and maybe saying, “I don’t like this. None of these characters look like me, and none of these stories look like mine.” Do we create space for these things to be said, for this failure of relatability to be teased out? Do the essays we read—in The New Yorker, in the New York Times, in Slate, in Hazlitt—do justice, in their interpretational thrusts, to the multiplicities of reading experience? Really, is there justice done in mainstream-media’s proliferation of essays written by largely white men and women about Ira Glass’s offhand response to Shakespeare?

I spent a long time yesterday reading Jed Perl’s essay “Liberals Are Killing Art.” I didn’t want to, but I fell into the trap, my siren song: the long, controversially-titled essay about art. Perl would claim ‘art and justice’ is a problematic linkage, same as ‘art in education’ or ‘art in society’ or ‘art and politics.’ He contests that art exists in an independent sphere, apart from, say, war or public education or you eating your ham-and-cheese sandwich at lunch.

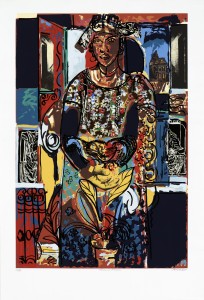

I find arguments like Perl’s tiresome at best, dangerous at worst. These are the same arguments that use statements like “art has transcendental power” to alienate lived experience from creative expression. These are also the arguments used to justify the egregious underfunding awarded, at least in this country, to artists and creative professionals who labor, just like the rest of us do, for something Perl relegates to the nebulous, the abstract, the “transcendental.” These are the arguments that call art “the imagination interacting with the world” while citing the work of mostly white male artists. It’s a posturing of empathy. It’s also a failure to acknowledge that ‘the world’ is made up of radically diverse people living radically diverse lives, lives that don’t fit into “easy platitudes about getting along and we’re all the same,” as Christian said in a recent Project Change email exchange.

I’m wondering a lot lately about how we create space in American classrooms for the sharing of stories and experiences that are not accounted for in the canon or in the mainstream. About how I think we have a responsibility to, as a friend said yesterday, a “conscious diversification of what we consume—from food to television to literature.” A responsibility to reach outward, to reject passive, self-reflexive relatability. I’m also wondering whether we can and should legislate the same for people whose races, ethnicities, cultural backgrounds, stories, ideas, feelings are still not granted significant (read: the space afforded to Shakespeare) space or authorship—whether in a curriculum or in a think-piece about relatability.

I’m wondering about my over-reliance on the “we,” about how it assumes universality. It also assumes that people want to try to relate to one another, to owe each other attention, an eager ear, space to be.

“We who?” This is Teju Cole’s Twitter biography. It is also a sly, biting mandate to be open. To call out postures of empathy and universality as, well, postures.

Twitter is an exercise in relatablity, in experimental empathy. I think it bends toward openness. Glass himself is a Twitter neophyte; he just “joined” this year. And with his Shakespeare tweets, Glass pouted, in the same way that many people (myself included) do from time to time on Twitter. Life is messy for all of us. For some of us, that messiness is compounded in ways that are, thanks to history, policy, curricula, social systems, media, et al., left dangerously dim to those of us who say “our canon” and think it represents the U.S.’s—and the world’s—actual demographic breakdown. I like to think Glass’s tweets were actually sly mandates to be open, to grant legitimacy to the idea that Shakespeare’s work could, for someone, feel unrelatable. That that feeling, and its articulation, are worth attention. That one day, that essay is the one we’re (emphasis on the “we”) sharing.