Rock Castle Home: An Appalachian Community Shares Their Stories

Duke professor’s new film illuminates the history of a 1930s farming community displaced by the Blue Ridge Parkway

On Friday nights, the small town of Floyd in southwestern Virginia (population 425) becomes a gathering spot to play and hear American traditional music. Decades ago, the Floyd Country Store started hosting an informal jamboree. Word spread, the crowds grew, and the store now boasts a state-of-the-art performance stage.

“People come from all over the world every Friday night,” says Charles D. Thompson, Jr., professor of the practice of cultural anthropology and documentary studies and a senior fellow at the Kenan Institute for Ethics. A musician himself, he often joins the jamboree.

“People come from all over the world every Friday night,” says Charles D. Thompson, Jr., professor of the practice of cultural anthropology and documentary studies and a senior fellow at the Kenan Institute for Ethics. A musician himself, he often joins the jamboree.

To learn who traveled the furthest, the evening’s host asks audience members to shout out where they’re from. When Thompson brought guests from China, he was sure they’d take the prize – but they were edged by old-time music fans from New Zealand.

Thompson lives in Durham now, but his roots are in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Born in Franklin County, not far from Floyd, he has traced his family history in the region back to the 1700s.

One Friday night during a break from the music, Thompson chatted with a friend who said his elderly father-in-law wanted to make one last pilgrimage to the site where he was born — a steeply mountainous area known as Rock Castle Gorge.

Matt Hubbard’s family and their neighbors, all farmers, had to leave the gorge to make way for the Blue Ridge Parkway, a scenic route established by the National Park Service in the 1930s. The woodlands in some areas around the parkway are protected as a national park.

Thompson, who owns a cabin nearby, eagerly joined the planned hike and asked a videographer friend to come along. “I had a sixth sense that it was important,” Thompson said. At 93, Hubbard needed some help from a four-wheeler to reach his birthplace, but he walked the final stretch. “I’m about the happiest man that can be right now,” he said on reaching the site.

Fascinated by Hubbard’s stories, Thompson embarked on a project to learn more about the displaced mountain farming community. Tapping into research done by a group of descendants, he found a surprising connection: his great, great grandfather had married into a Rock Castle family. “I have never felt as close to my ancestors as when I was doing this project,” Thompson said.

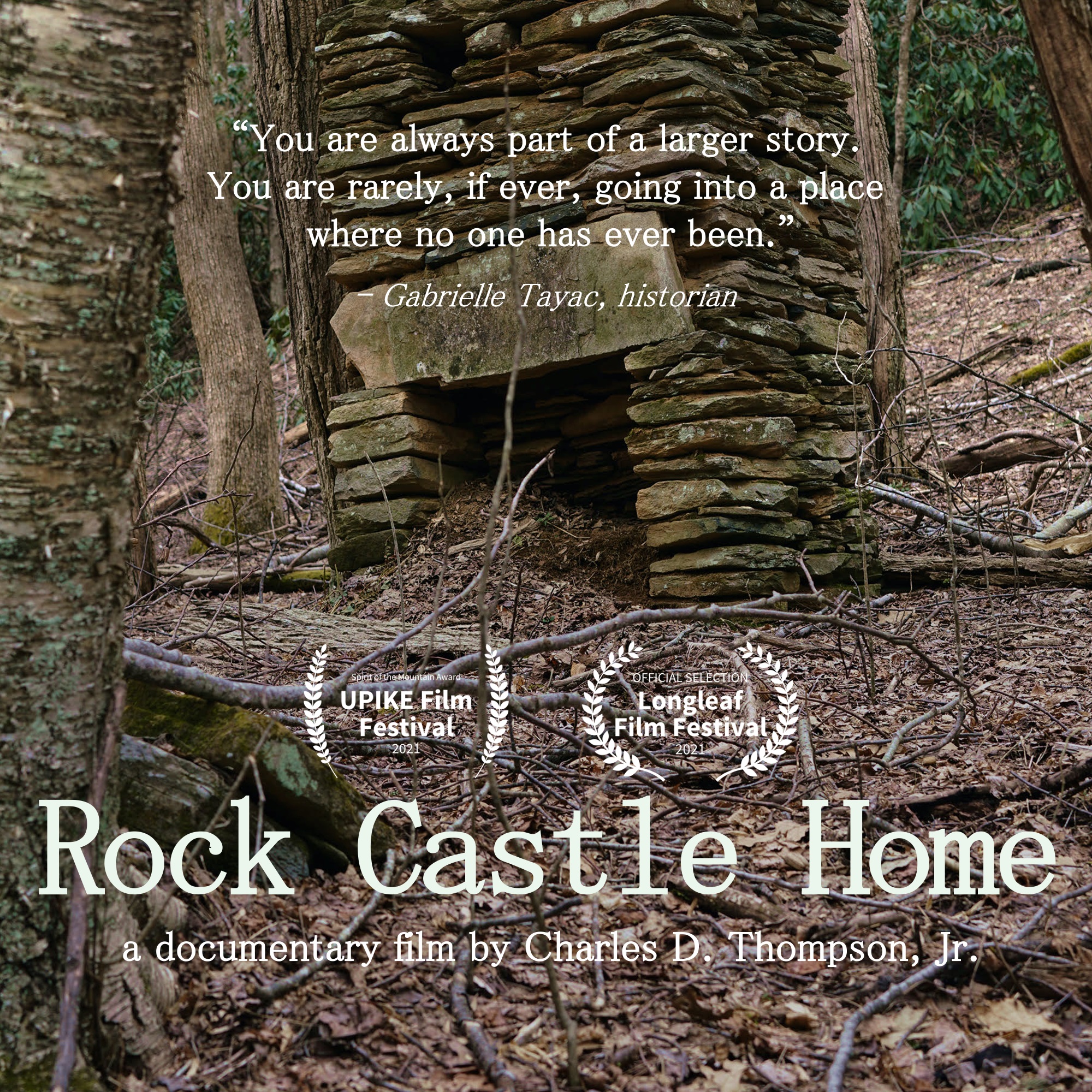

Thompson’s resulting documentary film, Rock Castle Home, is both personal and universal. Descendants share stories, photos and artifacts from the past, bringing the gorge’s bygone community to life. “It also tells the bigger national story of the Great Depression, Prohibition, the chestnut blight, the national parks system and the Blue Ridge Parkway,” Thompson said.

“It’s very different than Ken Burns’s approach to his series on the national parks, [which showed] a top-down view from Washington. We’re looking at this national park from the ground up.” Many community members, including some of the musicians Thompson plays with in Floyd, became collaborators on the film.

Today, 15 million people visit the Blue Ridge Parkway each year. Drivers along the 450-mile route are rewarded with magnificent views of verdant forests. Preserving this landscape and making it accessible to the public as a national park ensures that a vital part of America’s natural beauty is maintained for future generations.

Few visitors get a sense of the people who once lived there. “The average person driving along the parkway sees nature, not culture,” said Thompson. And too often, their perceptions of Appalachian communities have likely been colored by a limited range of TV shows, movies and books.

“The hillbilly is the last fair game for stereotypes,” Thompson ruefully pointed out. “In this film I have provided an example of how we can combat stereotyping by using a more nuanced approach.” He wants viewers to see how inventive these communities were. “It took incredible ingenuity for these settlers to come here and use natural materials to build and grow everything” on steeply rocky slopes, Thompson said. “People were quite artistic, too. We’re deepening a story about culture and creativity.”

The area was inhabited Before the European settlers’ arrival. “We address the Native American traces left there,” Thompson said, “and how the Saponi and others had to leave and join the Iroquois in New York.”

“When we preserve our cultural heritage, it builds a connection between the past and the future.

Future generations will have a better understanding of their heritage and will have a sense of belonging to a community.

In turn, the people and places of their ancestry will be respected, valued, and treasured.”

— Beverly Belcher Woody, Rock Castle descendant

Throughout the making of the film, Thompson sought to tell not just the story of Rock Castle but to show how the descendants went about preserving their family histories and unique cultural and historical identities. “If we don’t tell our story,” said local historian Beverly Belcher Woody, “someone else will …. or maybe the story will be forgotten altogether. We refuse to let that happen.”

Rock Castle Home premiered on Virginia public television on May 20. That evening, the Floyd Country Store hosted a watch party and celebration with live music. Taking the film back to where it was made, said Thompson, was “a wonderful homecoming.”

The Grandin Theatre in Roanoke will host a screening on May 29, accompanied by music and a Q&A with the filmmakers.

Virginia Public Media will make the film available to other PBS stations around the country, and Thompson hopes to organize screenings and events in the 2021-22 academic year for Duke and North Carolina audiences.

Rock Castle Home received funding from several Duke sources – the Kenan Institute for Ethics, Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, Center for Documentary Studies and Bass Connections.

This piece was originally written by Sarah Dwyer for Duke Today. The piece can be accessed here.