Spinning the Great World: On Failure, Empathy, and the Life of the Humanities

By Michaela Dwyer

“There was a dip before the laughter, a second before it sank in among the watchers, a reverence for the man’s irreverence, because secretly that’s what so many of them felt–Do it, for chrissake! Do it!–and then a torrent of chatter was released, a call and response, and it seemed to ripple all the way from the windowsill down to the sidewalk and along the cracked pavement to the corner of Fulton, down the block along Broadway, where it zigzagged down John, hooked around to Nassau, and went on, a domino of laughter, but with an edge to it, a longing, an awe, and many of the watchers realized with a shiver that no matter what they said, they really wanted to witness a great fall, see someone arc downward all that distance, to disappear from the sight line, flail, smash to the ground, and give the Wednesday an electricity, a meaning, that all they needed to become a family was one millisecond of slippage, while the others–those who wanted him to stay, to hold the line, to become the brink, but no farther–felt viable now with disgust for the shouters: they wanted the man to save himself, step backward into the arms of the cops instead of the sky.

The watchers below pulled in their breath all at once. The air felt suddenly shared. The man above was a word they seemed to know, though they had not heard it before.

Out he went.”

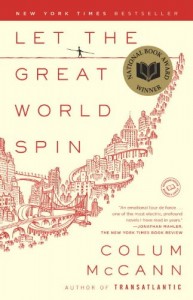

(Colum McCann, Let the Great World Spin, 5-7)

Two weeks ago, the writer Colum McCann perched at a podium in the renovated Baldwin Auditorium and invoked an audience of about 200. The bulk of the crowd were members of Duke’s Class of 2017, for whom McCann’s 2009 novel Let the Great World Spin was chosen as their summer reading book. The other contingent was a hodgepodge: community members, older students, interlopers like me who either read the book and liked it or wanted to hear a good speaker or both.

McCann commanded the room with an essence that slowly unfurled itself in the same way his writing does. His arrangement of words—as in the excerpt above, which preludes Let the Great World Spin—has a movement unlike any other I know. This quality makes it difficult to adequately excerpt sections of his text: each word, phrase, and sentence is both syntactically and semantically reliant on every other one. Descriptions and sentiments don’t end; they tumble together in the spin of his great [literary] world, in a way that feels at once magical and so natural as to be obvious, even mundane.

It makes sense, then, that McCann would incorporate a word game— Hangman—into his talk (“it’s four letters, it begins with an ‘F,’ and it’s not what you’re thinking,” he said as the students snickered). The word was “fail,” an especially uncomfortable term for Duke students. And especially for incoming Duke students, who barely know what life looks like, or could look like, at this university, but who are already attuned to the ways in which their efforts toward that end could “fail.”

Ironically, every aspect of this event felt successful. McCann established just the right rapport with his audience. The students had faithfully read and dog-eared the novel. They dialogued thoughtfully both with McCann and with each other, asking questions that often reflected complex considerations of his characters: What if so-and-so hadn’t died? Would he have taken his interest in social justice to South America, to advocate for others there? Why write the novel through multiple protagonists in the first place?

Irrespective of the specific text, the summer reading book is an institutional practice. It’s designed as a “shared intellectual experience” outside of, and in fact preceding, curricular learning. It’s strategically placed alongside other Orientation Week events like Southern-style dinners, wellness advice, and pre-X-future-career open houses. The hoopla surrounding a summer reading book is emblematic of what a Duke education could—even, perhaps, should—look like, before students slide into normative behaviors and patterned ways of engaging in university culture both in and outside the classroom.

McCann precautioned that he wasn’t there “to make grand pronouncements,” but went on to enumerate the three components of what, for him, make a “good” education: vision, justice, and charity. And…failure? I’ve noticed that Duke students often conceptualize failure in terms of performance outcomes: a poor grade on a test, a rejection from a summer internship, an unextended party invitation. In the opening lines of Let the Great World Spin, McCann posits failure in a similar way: the crowd gathered below the man on wire wants to witness a “great fall,” an action they’ve already determined to be “wrong.” When reading, we feel as though we’re there, on the streets, in the sweaty human hodgepodge of late-summer New York City circa 1974. We’re trapped, along with everyone else, within the immense tension between desire and action: we want the walker to fail, to fall, because that’s a very concrete and easily imaginable physical possibility. Little do they (we) realize, McCann implies, that the crowd’s collective imagination of failure—of the walker falling—has already bonded them (us). There’s still the imagined action of the walker, but now there’s also the action of us, together, breathing, watching, on the precipice of continuing the rest of our lives. “Out he went”; out we went, out we go.

There’s a lot of discussion (emphasis on “discussion”) right now about the humanities existing on a similar precipice. The humanities are in “crisis,” life-or-death mode. Does literature make us better people? Does teaching the humanities make us better people? Does assigning a summer reading book—Let the Great World Spin, to be specific—make us better people?

These are enormous ethical questions, steeped in abstracted assumptions of what is “good” and “bad,” what is “better” or “worse,” what is “success” and what is “failure.” To begin to answer them requires a complex moral imagination, the same one we begin to reach when we read a book like McCann’s, feel the characters as real people and empathize with them, and sit with each other on the edge of plush seats in a swanky college auditorium as an Irish writer tells us we all need to fail more. When we are able to “inhabit new geographies,” as McCann said in his talk, we expand our notion of what’s possible. Expansion is action, and, as in all matters of life, we have to act—perhaps with the intention, or assumption, of failure—in order to survive. Similarly, today more than ever, the humanities must act, and must be treated as actionable—in order for them to survive. Treating literature as “equipment for living,” as a great English professor at this university once said. This fall, as Kenan embarks on Duke-wide initiatives explicitly targeting ethics and the humanities, I’m excited to put this approach into play. The university campus is our space to experiment, act, and, yes, fail—and keep going. Besides, there’s a reason McCann’s book isn’t called “Let the Great World Rest in Perfect Order.” Life doesn’t look like that—whether within or outside the university—and I’ll dare to make the ethical leap and demand that it should not.