Letter 2 – Adventures in Surrealism

“Chagall’s…poignant, eternal world, radiant like a window opening from the darkness of our souls into bright blue skies, filled with flying fiddlers, green-faced lovers, and mysteriously smiling cows.”

— Olga Grushin, The Dream Life of Sukhanov

This week I read a novel that delighted and moved me: The Dream Life of Sukhanov (2005) by Olga Grushin. Sukhanov is the middle-aged editor in chief of the leading Soviet art criticism journal, where he pleases the Ministry of Culture with articles like “Surrealism and Other Western ‘Isms’ as Manifestations of Capitalist Insolvency.” About 25% through the book, I felt quite disappointed by it, because the characters had minimal psychic depth. Since Grushin seemed interested only in lyrical images, I resented her for writing a novel instead of a poetry collection.

But when I told my mentor, Professor Apollonio, that I probably wouldn’t finish the book, she advised me to continue reading. I did and learned that the same Sukhanov who wrote “Surrealism…cherishes madness and cultivates indifference toward the social good” privately adored surrealist art. In his youth, he’d been a talented artist inspired by surrealists like Dalí and Chagall, but abandoned his creative passion for the safer profession of art criticism. I realized that this book did have fascinating things to say—not about Sukhanov, but about art. By depicting moments of psychic transformation and transcendence through sensations of art, Grushin expanded my prior conception of art’s capacity for meaning making.

Last week I misunderstood the babushka in the grocery store by paying no attention to her psychic depth; this week I misunderstood the book by reading it exclusively for its psychic depth. But in both cases, my first and immediate hermeneutic lens was the agenda I had set before encountering the object. Instead of reading the book in front of me, I tried to read the book I wished were in front of me, i.e., a deposit I could mine for psychological insights.

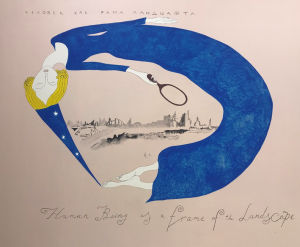

I loved the book once I began reading it as a study of the transformative potential of art, specifically, surrealist art. Surreal images, dreams, and memories perpetually invade Sukhanov’s stable life and force him to confront his repressed artistic past. They shock him out of his chronological self by liberating a host of momentary selves overcome with the admiration of art. But as Sukhanov loses interest in his prestigious career, his momentary selves are shown to alter his chronological self, rather than simply suspend it. These meddlesome selves frustrate, destroy, and finally reinvent his chronological self and the novel concludes with him becoming an artist again. This was why the book could not have been a poetry collection: only the temporal flow of a novel could encapsulate art’s chronologicaltransformation of the individual psyche.

Ironically, I only learned something new about the psyche by abandoning my psychic mining expedition. My conception of where I might find psychic depth had been too narrow. The introspection of characters? Yes. Their sensations of colors? Please. After reading The Dream Life of Sukhanov, my notion of hermeneutic generosity is no longer simply trying to understand the other, but also allowing the other to shape the very meaning of “understand.” My linear model of insight-finding was replaced by a detour model, in which generosity is the willingness to embark on the detours suggested by others. “Alright, I will see what you have to say about surrealism, even though I’m not sure it fits into my goals.” These detours through “blue skies, filled with flying fiddlers, green-faced lovers, and mysteriously smiling cows” cease to be detours as they become sources of psychological insight, paths to the original destination. Perhaps we can never see art or books or people as they truly are, but we can at least try to see them as they think they are, instead of as we think they ought to be.