Letter 1 – AMANDLA: A journey to PAN-AFRICANISM

It has been over a year since #Repeal162 was trending amongst Kenyans on Twitter — a virtual revolution against article 162 and 165 of the Kenyan Penal code that punishes homosexuality with up to 14 years in prison. On 24th May 2019, a large crowd assembled outside the Milimani Law Court in Nairobi awaiting the ruling by the High Court of Kenya that included Queer activists, lawyers, artists, and even Queer students like myself. However, there were also anti-queer people in attendance such as church leaders, lawyers, the police among others. The High Court ruled against decriminalizing these articles and as I stood by the door, barely able to hear all that the judge was saying, I saw a woman holding a Bible say aloud, “Glory to God.” I left the court greatly disappointed and wept on the matatu[1] ride back home. I wept for the weight of the world that had descended upon my shoulders and felt unbeaarable. I wept for my life, and that of others like me, was deemed unworthy, I wept for my friends – closeted and out, and for their partners and lovers. However, later that evening I decided that I had to do something to follow in the steps of all the Queer leaders before me who were at the forefront of this battle against the state. As Queer Kenyans, we are always constantly battling against Kenyans’ understanding of our bodies imposed upon us through the systems that were set up during colonial times. These systems have evolved over time under a neo-colonialist global network that Kenya, like many Sub-Saharan African, nations at large, mimics from the West — what Kwame Nkurumah described as the “African problem” writing on neo-colonialism as the final stage of imperialism in 1965 . “The essence of neo-colonialism is that the state which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty.” He writes, “In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.” It was therefore no surprise that the presiding judge declared a lack of evidence of extensive discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity throughout the country. This was an uncritical ruling that did not take into account the violence that occurs within the colonial institutions that Kenya continues to uphold: gendered boarding high schools, the church, the police and corrupt government. Queerphobia in Kenya perpetuates violence behind closed doors while simultaneously erasing it from the public as these colonial institutions refuse to document it as violence or offer protections to the victims.

It has been over a year since #Repeal162 was trending amongst Kenyans on Twitter — a virtual revolution against article 162 and 165 of the Kenyan Penal code that punishes homosexuality with up to 14 years in prison. On 24th May 2019, a large crowd assembled outside the Milimani Law Court in Nairobi awaiting the ruling by the High Court of Kenya that included Queer activists, lawyers, artists, and even Queer students like myself. However, there were also anti-queer people in attendance such as church leaders, lawyers, the police among others. The High Court ruled against decriminalizing these articles and as I stood by the door, barely able to hear all that the judge was saying, I saw a woman holding a Bible say aloud, “Glory to God.” I left the court greatly disappointed and wept on the matatu[1] ride back home. I wept for the weight of the world that had descended upon my shoulders and felt unbeaarable. I wept for my life, and that of others like me, was deemed unworthy, I wept for my friends – closeted and out, and for their partners and lovers. However, later that evening I decided that I had to do something to follow in the steps of all the Queer leaders before me who were at the forefront of this battle against the state. As Queer Kenyans, we are always constantly battling against Kenyans’ understanding of our bodies imposed upon us through the systems that were set up during colonial times. These systems have evolved over time under a neo-colonialist global network that Kenya, like many Sub-Saharan African, nations at large, mimics from the West — what Kwame Nkurumah described as the “African problem” writing on neo-colonialism as the final stage of imperialism in 1965 . “The essence of neo-colonialism is that the state which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty.” He writes, “In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.” It was therefore no surprise that the presiding judge declared a lack of evidence of extensive discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity throughout the country. This was an uncritical ruling that did not take into account the violence that occurs within the colonial institutions that Kenya continues to uphold: gendered boarding high schools, the church, the police and corrupt government. Queerphobia in Kenya perpetuates violence behind closed doors while simultaneously erasing it from the public as these colonial institutions refuse to document it as violence or offer protections to the victims.

This moment was a turning point for me as a Queer Kenyan. I decided to use my education and skill as a storyteller to empower other Queer Africans by enabling us to develop stronger networks amongst ourselves. Therefore, after returning to Duke University for the fall semester, I was able to advance my knowledge of feminst theory as well as get involved in various art communities on campus. All my favorite readings and books were the ones that explored theory through real-life events; material through which I was able to be critical of systems, and history. I enjoy reading Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Franz Fanon, Saidiya Hatrman and Edward Said who transformed my understanding of history to be a contemporary perpetuity inextricable from the past. While they write extensively on different topics, their work enabled me to be critical of historical epistemology by encouraging me to always ask’ how come?’ This has enabled me to see how the past is heavily interconnected with the future. I learn a great deal from Judith Butler, Kimberlee Crenshaw, Donna Haraway, Angela Davis, James Baldwin, Anne Fausto-Sterling and Sarah Ahmed who informed my perspective on race and queer theory. My perspectives on African politics are greatly informed by Dr. Wandia Njoya, Albert Memmi, Kwame Nkurumah, W.E.B Dubois, Aime Cesaire, Achille Mbembe, Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Merged together, all their works provided me with a new understanding of the world — it was like they gave me a pair of glasses through which I now see and understand the world I currently navigate as a rising junior student in America. It allowed me what many years of schooling did not, the ability to question and think critically about identity, world history, and creatively about problem-solving. This is the potential of education. In transitioning from the theory I studied in the classroom to praxis, I was especially fascinated with listening to people’s stories as a way of engaging with the world that took into account this new perspective. As I listen to people, I can see how these systems that run the world such as education, healthcare, governments, and religious congregations exist under the world’s capitalist mode of production and tangibly impact people’s lives. By critically interrogating this capitalist mode of production we are able to better understand how Black people were enslaved, are imprisoned, and Indigenous people are dispossessed of their land during colonialism. Furthermore, we can understand how neo-colonialism and systematic racism continues to negatively impact Black and Indegenous People of Color (BIPOC) in the United States. Like in the rest of the world, they are ‘imprisoned’ under a colonial perpetuity. Therefore, I began to write and assemble other Black students on campus to share their stories with me. Accordingly, I launched Khaya Magazine under DukeAfrica, a student-organization that fosters community among African students on campus. Khaya features the stories and art of Black and African students on campus bridging across multiple networks, organizations, departments, and schools. My greatest lesson from this experience was that storytelling is truly one of the greatest forms of activism. This is the power of education.

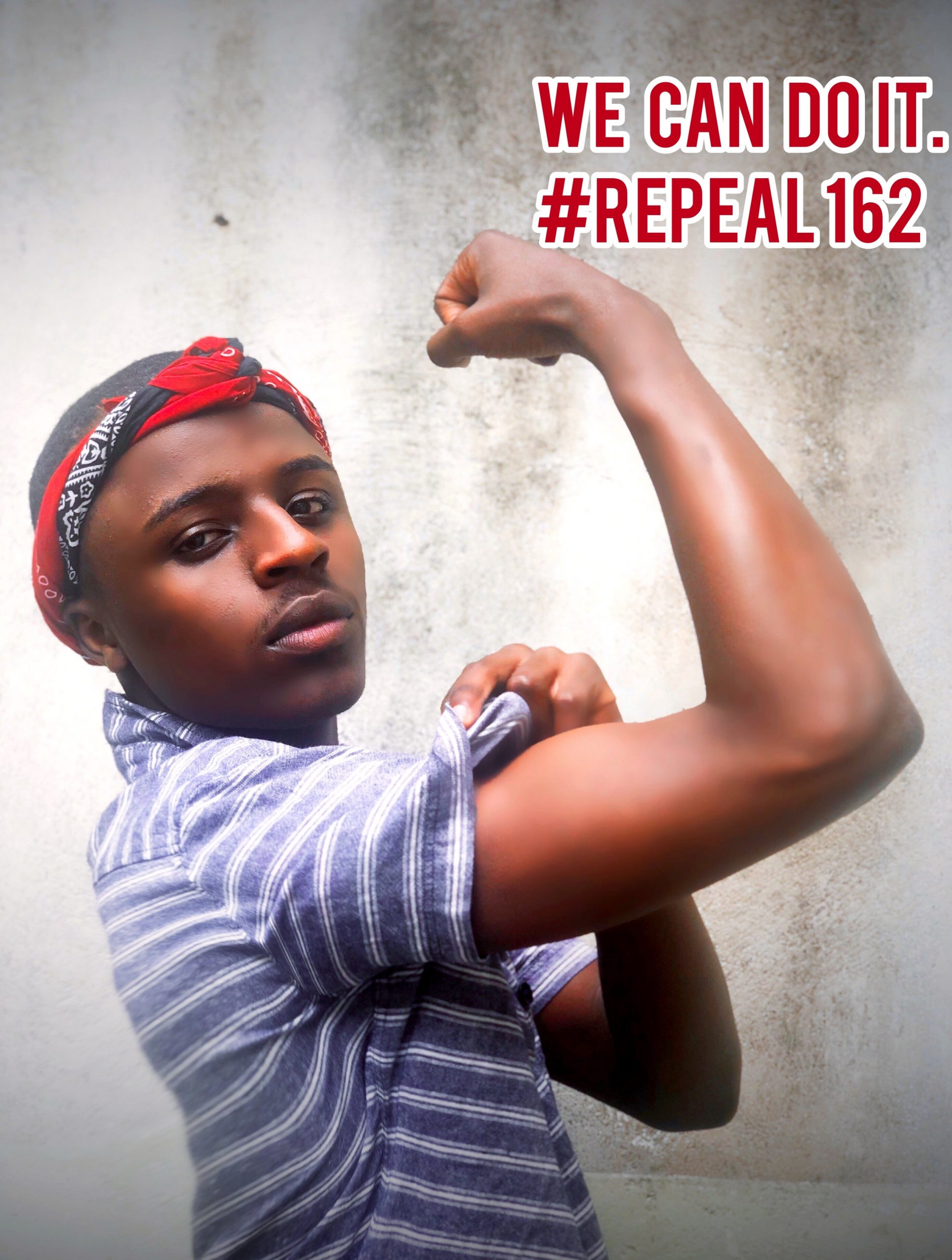

This experience is what led me to apply for the Summer Fellowship Program offered by Kenan Institute for Ethics to create the premiere digital archive of TLGBIQ+ resistance across Africa, starting with countries in East and Southern Africa. While it took a while to get individuals who were willing to share their stories with me, resilience is a storyteller’s master key. I took to the internet where we have created our own communities through transnational following —Twitter, Instagram, Facebook etc. I also reached out to organizations working to serve Queer communities to seek support. By sharing my open call to Queer people in their directories, I had a variety of groups and individuals to collaborate with. By allowing anonymous submissions to ensure security of people who would otherwise be endangered, we received multiple submissions. Our recorded interviews are conducted via end-to-end encrypted zoom calls and consenting participants are allowed to submit pictures if they can. Furthermore, by collaborating with other organizations, I have secured support for Queer participants who have never taken professional pictures before to do so for our magazine publishing this August. A life-long project, I am merging storytelling, photography and audio-recording on QueerAfricanNetwork (QAN), a social professional networking site, created by the brilliant Okong’o Kinyanjui, that will enable anyone to access Queer African stories, communities, and a database of opportunities vetted to be safe for Queer Africans. As one of QAN co-founders, I will curate stories, books, podcasts, pictures, videos and playlists for Queer Africans by Queer Africans on QAN. To this end, I will also be launching a magazine, AMANDLA, and radio station called MASHOGA, which will showcase the stories of Queer Africans starting with Eastern and Southern Africa. AMANDLA Magazine goes live on our website in September. MASHOGA Radio’s first program goes live in January, and will be accessible on Youtube and other platforms. We will expand to other regions accordingly over time. Finally, I am also publishing my first anthology of poems, The Gender Binary is a Prison that reflects my personal journey to becoming a queer non-binary artist (feel free to use any labels and pronouns from this binary prison.)

In documenting these stories, I hope to offer insight into a more critical understanding of queerphobia in Africa and the world that is not disengaged from our mode of production and this colonial perpetuity. In order to offer restorative justice to any marginalized populations, especially Queer Africans, we must employ intersectionality into our praxis. Intersectionality is a theoretical framework developed by Kimberlee Crenshaw, for understanding how aspects of a person’s social and political identities might combine to create unique modes of discrimination and privilege. AMANDLA and MASHOGA, in line with the mission of QueerAfricanNetwork will empower Queer people from various disciplines, activist forms, and countries in the hope to build coalition work that goes beyond the neo-colonial borders that divide Africans. If Africa will ever realize Pan-Africaninsm, Queer people must be at the forefront of the movement. In pursuit of a Pan-Africanist future, AMANDLA will take after the virtual revolution started by #Repeal162 through activist storytelling. Amandla Awethu ! Power to the People! Power to Queer People!